On a humid Orlando night in March 1985, sports reporter Joan Ryan entered the United States Football League’s Birmingham Stallions’ locker room after their 34-10 win over the Orlando Renegades. About 70 sweaty football players filled the room, all in different stages of undress, cutting off athletic tape, some throwing jock straps. The players’ stench hung in the air, thick as lard. Ryan, then in her twenties, hoped to interview running back Joe Cribbs, who had broken his wrist just before halftime. She’d been in a locker room before, but in 1985, not many female reporters had. The players yelled obscenities at her. Ryan, paralyzed with fear, stood in the doorway. One player ran the handle of his razor up her leg, to the bottom hem of her skirt. Appalled, Ryan turned to leave, and caught a man wearing a red, V-neck sweater chuckling at the ordeal. She would later identify the man as Jerry Sklar, general manager of the Stallions, and wrote in her weekly column for the Orlando Sentinel, that Sklar “stood by like a father who claps his son on the back after every cruel prank and declares, with a touch of pride, that boys will be boys.”

After that night, Ryan knew she wanted to be a sports writer.

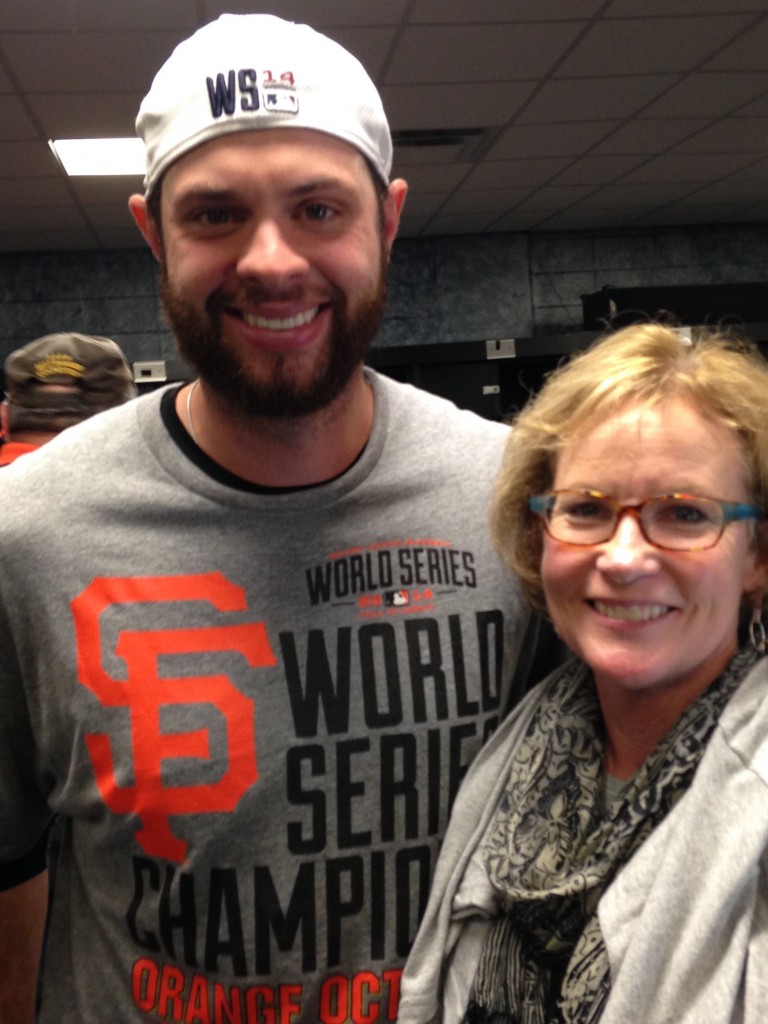

She would go on to have a 25-year career in daily journalism, writing first for the Orlando Sentinel, then the San Francisco Examiner and San Francisco Chronicle. She is currently a media consultant for the San Francisco Giants, and has written four books. She is most proud of her first book, “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes: The Making and Breaking of Elite Gymnasts and Figure Skaters,” a controversial investigation of the physical and mental harm suffered by young female athletes, not unlike the findings published last August by The Indianapolis Star, which exposed USA Gymnastics’ passivity in responding to allegations of sexual abuse within the organization.

Ryan’s “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes” generated waves in the sports world, leading to USA Gymnastics’ creation of a coaches’ credential training program and a parent handbook that highlighted the hazards of competing on an elite level, including injuries, eating disorders and abusive coaching. “Nothing I ever write will have that kind of impact,” Ryan said of the book.

Exemplified by “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes,” Ryan was always bold in her reporting. “Every piece of work you do is the most ambitious thing you’ve ever done,” Ryan said. “If you’re going to do it well, you’re never comfortable.” Former SF Chronicle metro editor, Ken Conner, characterizes Ryan as a “courageous” reporter. A friend of Ryan’s, Lorna Stevens, said Ryan is “fearless,” “a trailblazer.” Stevens and Ryan have been friends for more than 20 years and their kids grew up together. Conner recalls Ryan, as a columnist for The Chronicle, researched the OxyContin painkiller epidemic in 2003 by buying the prescription drug from a dealer in one of San Francisco’s highest crime neighborhoods, the Tenderloin. “She walked in and got her column,” Conner said.

In another escapade, Ryan was writing a column about body modification. It was the early 2000s in San Francisco. At about 10 p.m. one night, Ryan visited a bar in which to conduct her research. The bar was smoky and dimly lit. Sawdust coated the floor. Large spotlights illuminated people below, specimens of body modification, including one man with his lower ribs removed. An androgynous couple, one wearing a collar, the other holding a leash, trotted around the bar. A phone sex worker displayed large, dangling nipple rings. Ryan was unmoved. She began interviewing people. A line formed. People wanted to talk with her. When Ryan interviews, it’s like “you’re the most important person in the world,” Stevens said.

On the surface, Ryan is small in stature, 5-foot-3, red hair cut short, her lipstick the color of a strawberry milkshake. She emits a kind of motherly warmth. She wasn’t born the scrappy journalist that she is today. As the third child of six, growing up in Ridgewood, New Jersey and Plantation, Florida (just west of Ft. Lauderdale), Ryan was shy, a self-described introvert and a tomboy. “I thought, ‘boys had so much freedom,’” said Ryan, remembering a time when she flung herself onto her bed and yelled, “I wish I was a boy!” Although Ryan was an attentive student and read ardently, she never raised her hand in class and was the kind of child to have only one close friend. Her father, Bob, a loud Irishman and girls’ softball coach, was her connection to sports, and her biggest fan. Upon meeting Ryan’s now husband (sportscaster Barry Tompkins) for the first time, Bob said to Barry, “she’s got a really quick swing.” Ryan viewed her mother as “without a voice,” and as a young adult thought, “That’s never going to be me.”

At 9 years old, in one of her father’s company picnic baseball games, Ryan played in the outfield. She recalls a young man, perhaps one of her father’s co-workers’ sons, sent a line drive screaming toward her. She caught it, and her father yelled excitedly. He was proud of his little girl. “This was the value in his eyes. It’s not just being good at sports — it’s being bold, stepping up, proving people wrong about me,” Ryan said. The best advice her father ever gave her, she said, was to think, “once you step on the field, you better hope the ball is coming to you. Nobody is better prepared.”

Later, Ryan would take that attitude into the press box as a sportswriter covering multiple Super Bowls, the Olympics and the World Series. As a budding sports reporter, and one of the few female sports reporters in the late 1980s, Ryan questioned her abilities in a career dominated by men. In times of doubt, she returned to her father’s lessons. At more than one Super Bowl, Ryan sat in the press box, and told herself, “Oh my God. I can’t do this. But you can be someone else who can.”

Ryan’s message to young girls, shy or not, is to play sports. “Play team sports because it will teach you to take risks. Because guess what? You’re going to fail, a lot,” she said.

Graduating with a degree in journalism from the University of Florida in 1981, Ryan was the first in her family to attend college. Before move-in day, Ryan had never seen a college campus.

“It was an incredible opportunity that so many people didn’t have,” Ryan said. She thought, I better do something with it. Ryan helped pay her way through school by waitressing and by working a job that required her to empty nickels from the libraries’ Xerox machines. Three days after graduation, Ryan began her career as a copy editor at the Orlando Sentinel.

Ryan always had a radar for injustice; as a child, she recalled picking up sexism in the teachings of her civics teacher, Mr. Kegley, also the school’s football coach. Following her 1985 column about the incident with the Birmingham Stallions and Jerry Sklar, Ryan received mostly negative mail from readers, attacking her presence in the locker room. Rather than shut her down, this reaction only fueled her. Her first book, “Little Girls and Pretty Boxes,” may have been the climax of her outrage with injustice. Toward the end of writing “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes,” Ryan felt “suffocated” by the stories of eating disorders, injuries and abuse. While she was writing the book, one of the gymnasts died from anorexia. According to Stevens, after Ryan finished the book, she said she’d never write another.

Her perspective as a writer changed, however, when she became a mother in 1990. Now, she describes herself as more compassionate. In 2006, her then 16-year-old son, Ryan Tompkins, suffered a near-fatal brain injury in a skateboarding accident. “The most important thing she realized was, the child needed to live,” Stevens said. Throughout her son’s recovery, which Ryan writes about in her 2010 book, “The Water Giver: The Story of a Mother, a Son, and Their Second Chance,” Ryan never lost her identity as a journalist; on a medical chart kept at the foot of her son’s bed in the intensive care unit, nurses wrote, ‘mom asks a lot of questions.’

As a result of motherhood and her son’s accident, “I learned how much is out of my control,” Ryan said. “That’s kind of freeing.”

Motherhood allowed Ryan to redefine failure. Now, she can look at failure without judgment, and learn from it. And when it comes to writing, she doesn’t need to pretend anymore. Once a child with a fear of talking in class, Ryan now loves public speaking. And according to Tompkins, she’s now “one of the guys.”

Although Ryan thinks fondly of her introverted, early-career self who relied on her father’s “fake it till you make it” attitude, she isn’t that person anymore.

“I’m the best part of that girl,” Ryan said. “And I’ve made it.”

CORRECTION – Editor’s Note (5/18/2017): In this story originally published May 17, 2017, Peninsula Press misspelled and misidentified Jerry Sklar, who was the general manager of the Birmingham Stallions. The above story is updated.