Pillar Point Harbor, the jumping-off point for the world-famous Titans of Mavericks big-wave surf contest has postcard views of the Pacific Ocean. Monster waves rise up over the horizon and white hills of froth and foam crash down over the break. It’s an iconic California scene. But lurking just below the surface of the harbor’s waters are some of the highest fecal bacteria levels found in any beach in Northern California.

Beaches line the harbor inside the breakwaters. One of the beaches made the Heal the Bay “Beach Bummers” list in the most recent report card — the fourth time since environmentalists started rating the water quality at the beach. The West Point Avenue beach has the ninth-worst water quality in the state out of over 600 beaches.

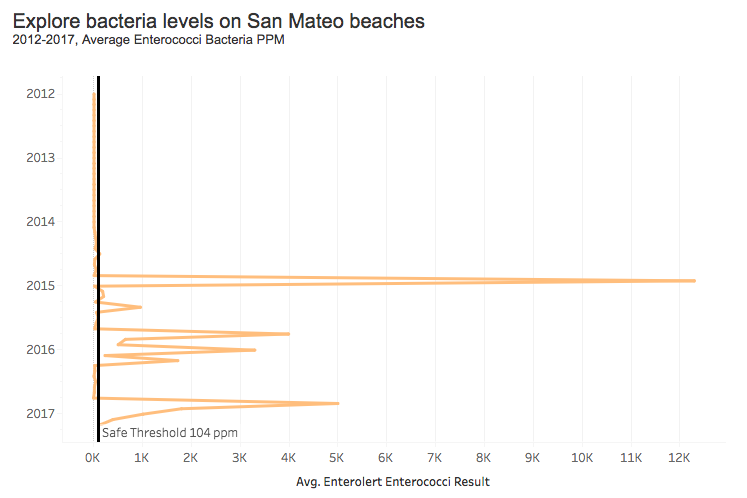

But the problems go way beyond the Beach Bummers list. A Peninsula Press analysis of water sampling data shows the water quality problems at Pillar Point Harbor are chronic. The safe threshold for Enterococcus bacteria levels — that’s the bacteria found in feces — is below 104 units per 100 milliliters. Beaches in the harbor regularly hit levels above 1,000, even spiking off the chart at over 24,000 ppm last fall.

“As long as you don’t fall in, you’re fine,” said Naomi Feger of the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

Health officials have been trying to figure out the source of the bacteria at the harbor beaches for years. They sent investigators out into the harbor, sampling water from the docks and looking for boats dumping raw waste. Other investigators searched for leaks at the pump station where boats empty sewage tanks.

But as it turns out, the culprit is more mundane. It’s wildlife, like deer. It’s dog droppings from people’s yards and walking paths. Waste flows into the harbor and lingers in the sand. Pillar Point Harbor has multiple watersheds that flow into the bay in both wet and dry weather that are like microbial freeways speeding bacteria to the harbor.

“If it comes from wildlife and nature, nobody’s responsible,” said Kellyx Nelson, executive director of the San Mateo County Resource Conservation District.

The green sloping hills of Montara Mountain send rainwater down into the amphitheater-shaped community of El Granada. Water flows through backyards, over driveways and down into the roads. Water trickles into the small streams called watersheds, then into pipes that run under the parking lots and seafood restaurants, and into beachball-sized pipes where it is finally delivered to the bay. Flocks of seagulls float, turning slowly in the dark brackish mixture of fresh and salty water pouring out of the pipes. It all works together to create a petri dish where bacteria lives and blooms.

Storms wash waste, dirt and anything else found on the ground into the ocean, said Greg Smith, who manages beach water testing for San Mateo County. Health officials urge people to stay out of the ocean for three days after it rains.

“There’s all kinds of stuff in the water,” Smith said.

Bacteria concentrates in watersheds, said Leslie Griffin, a water quality scientist at Heal the Bay, but once the creek hits the open ocean, bacteria levels drop off. The negative impact of rain on water quality is so significant, said Griffin, that the organizations evaluate beaches in both wet and dry seasons separately.

Capistrano Beach

[dropcap letter=”A”] sea lion floated just below the pier, barking at people fishing from the pier and stealing bait. It’s lunch time, and back at Capistrano Beach, a line of people snaked out the door and onto the sidewalk at Barbara’s Fish Trap.

Capistrano Beach is the epicenter of the water quality problems facing the harbor. An analysis of water sampling records from the Surfrider Foundation shows Capistrano Beach has the highest bacteria levels, on average, in San Mateo County. County data also shows Capistrano and the harbor beaches have chronic problems with bacteria levels. But there is no simple solution to clean up Capistrano, a textbook example of the problems facing officials and environmentalists working to keep beaches clean and safe.

Sabrina Brennan said she sees children playing at Capistrano Beach every weekend and worries they don’t realize the danger of the contaminated water.

“I see families with small children playing in the water right next to the signs that say warning contamination,” said Harbor Commissioner Brennan. “It used to really upset me.”

The beaches are sheltered and calm. Parents don’t want to take their children to the nearby ocean beaches because of sneaker waves and strong surf, said Brennan. Parents want to take their children to a safe place.

It’s counterintuitive for parents, said Griffin, but enclosed beaches — like bays and harbors with natural or artificial breakwaters — can be the worst places to swim because of the high bacteria levels, especially for children. The three other beaches in San Mateo County that received a C, D and F on the Heal the Bay report card are also enclosed beaches.

On a cloudy but calm day, Keith Mangold, a volunteer water tester for the Surfrider Foundation, leaned over the sidewalk railing on Capistrano Road to look at the pipe where the Capistrano watershed drains onto the beach. A seagull sat in the sand near the tiny freshwater river. The gull looked shabby and listless.

Tourists sipping pints of beer across the street watched Mangold through the glass windscreen. He pointed out the tarps from a transient camp tucked away in the bushes. On the left of the beach, two pipes from the St. Augustine watershed dumped runoff into the harbor between the beach and the pier. A line of trees to the right marks where Denniston Creek flows through an open field then out to the harbor.

Once a week, Mangold and other Surfrider volunteers sample the water in a plastic vial that looks like a clear 35mm film canister. He puts the samples into an insulated lunchbox and drives back to an old pump house turned ad-hoc lab. The water is mixed with a nutrient solution and poured into what looks like an empty blister pack for pills the size of a rubber school eraser. This is passed under a blacklight. One blister lit up, indicating the bacteria level, which Mangold records with a pencil in a three-ring binder.

Water quality is a moving target impacted by both structural issues and one-off events. Surfrider once discovered a couple of RVs draining into the San Vicente watershed. “Sheriff took care of that one,” Mangold said.

Transient populations sometimes use creeks as a bathroom, Mangold said. And bacteria spikes after the first rainstorm of the season — the “first flush.”

Bacteria gets caught in biofilm, the scum that floats on top of the water, according to a 2014 report commissioned by the state and the county. Bacteria also gets caught in the sediments of the beach, which is then re-released when there’s “turbulence” in the water, the report said. It’s as if the beach is a sponge that is saving up bacteria and releasing it later.

It’s hard to pin down the source of the bacteria in the watershed, but once it gets into the harbor, said Brennan, a “cesspool effect” sets in.

Bacteria in the water

[dropcap letter=”T”]he bacteria tested in the water samples are indicators of other problems, said Smith. It means other microbes might be present in the water that could make people sick. The germs include salmonella, potentially deadly bacterium; giardia, a parasite that causes nausea and diarrhea; and cryptosporidium, protozoa that attack humans’ gastrointestinal systems.

Surfrider found norovirus in Southern California beaches. Norovirus is the same gastrointestinal virus that sends cruise ships back to port.

For every 1,000 surf sessions, 12 people caught stomach bugs when water quality was below healthy limits, a Surfrider study found. The same study found that fecal bacteria is correlated with illness — so the more germs in the water, the more likely people are to get sick from that water.

When bacteria levels are too high, San Mateo County posts signs on beaches warning swimmers to stay out of the water, Smith said.

“Families with children need to read the signage,” Brennan said.

Unsolved problems

[dropcap letter=”M”]angold side-stepped dog waste lining the steep asphalt drive, as he marched up the hill overlooking the point, from the Mavericks Beach parking lot. At the top, Mangold pointed out the valleys and watersheds that slump down into the harbor. The fog burned off, leaving a clear view of the harbor.

It will soon be summer again, and swimmers are heading to the beaches, but there’s no solution in sight. Cleaning up the watersheds that empty into the harbor isn’t on the state’s five-year horizon.

“As with everything, it’s always an issue with funding,” said Feger.

People have to walk on the beach at West Point Avenue, the chronic “Beach Bummer,” on the way to see the famous Mavericks surf break. Dog waste is a major culprit for West Point, said Mangold. The rain carries waste from dogs and animals into the bay. On the way back to his car, Mangold stepped over a short-hair Chihuahua relieving itself near the trail gate.

The official in charge of posting warning signs on San Mateo Beaches, Greg Smith, said he walks his nine-pound dog Ruby, a Maltese-Yorkshire mix he calls a “morkie,” along the coastal trails. He hands out plastic bags and asks dog owners to “please scoop your waste.”

The Harbor District has deactivated the committee that once focused on water quality, Brennan said. Educational signs or postcards could educate citizens about cleaning up pet waste in their yards. She also suggested more pet waste stations along the trails, and said: “I think the commission has a lot of work to do.”

San Mateo County could fund more water-quality testing and remediation. The Harbor District is funding ongoing investigations into the source of the poor water quality, but Nelson, from the county conservation district, said she doesn’t have a timeline as to when the answers will be found.

“It essentially is detective work,”Nelson said. “A detective can’t tell you when they’ll solve a case.”