In 2009, José Cabrera was stuck. He had recently been released from prison, returned to his hometown of East Palo Alto, and was trapped in a constant battle between his personal willpower and the systematic oppression of minority communities like his own. He’ll tell you that his life could have gone in a lot of different directions. Many of them would have landed him back behind bars.

“All I knew is I didn’t want to go back, but I didn’t know how I was going to do that change,” Cabrera said. “This turned out to be a blessing.”

By “this,” Cabrera means meeting David Lewis and participating in his East Palo Alto re-entry program. He will tell you that it took a few tries to get into it, that he was resistant at first (participation was mandatory for parolees like him living in EPA at the time, which made him skeptical). But the program eventually did what it was supposed to: it kept him away from prison and effectively changed his life.

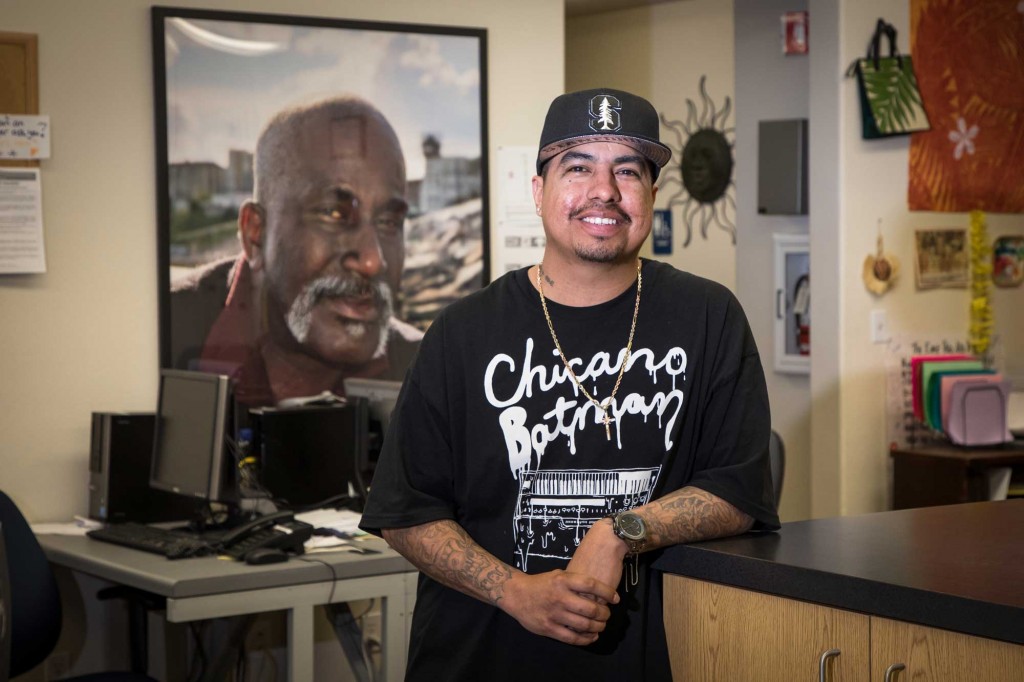

Today, Cabrera is a public speaker and a community worker at the David Lewis Reentry Center. Both on and off the clock, Cabrera draws upon on his own tumultuous past with the law to lead EPA youth towards a bright future and help locals recently on parole and probation brighten theirs. But if it weren’t for this series of events that unfolded as recently as eight years ago — if it weren’t for this program — his story could have had a very different ending.

This program has two unique characteristics that Lewis established at the onset. First, its services had to remain accessible to both parolees (who typically go to the state for support) and probationers (who are under care of the county) in EPA. Secondly, everything — every service and resource — had to be offered under one roof.

“The county provides these services, but not at one-stop shops like this. Here you see probation offices and parole offices working together,” said Carlos Morales, interim director of correctional health services for San Mateo County. He’d worked with the David Lewis Reentry Center when he was the clinical service manager for Service Connect, the county’s reentry and rehabilitative services network that the David Lewis Reentry Center officially joined in 2014.

“[The center] has given the county a blueprint on how to use resources from the state, the county and the city together,” he added. “It’s tailored to the reentry population.”

The David Lewis Reentry Program began as a collaboration between local community leaders David Lewis and Robert Hoover, the city of East Palo Alto, and the East Palo Alto Police Department. The concept behind the center was, and remains, to offer formerly incarcerated individuals support in re-entering the community after extended periods of time in jail and prison; programming was initially based off of Lewis’ own experiences returning to EPA after 17 years in and out of prisons across the state. Eventually, the program came to include mental health services, drug and alcohol counseling, career development, vocational training and housing assistance. When Lewis died in 2010, the program and the building it’s now housed in was renamed after him in honor of the groundbreaking work he’d done for the community.

For the re-entry population in EPA, these services are sorely needed. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s 2015 Crime in the United States report, San Mateo County reported a total of 330 violent crimes that year: 181 of those crimes — over half in a county hugging the entire east side of the Bay Area Peninsula, from Daly City to the Portola Valley — fell in East Palo Alto’s jurisdiction. Compare these rates to those of EPA’s neighbor across Highway 101: in 2015, there were 68 violent crimes reported in Palo Alto, a city with a population over twice the size of EPA’s. In a small, sometimes volatile community like EPA’s, parolees and probationers from EPA can fall back into a pervasive cycle of crime and imprisonment. Localized programs like those at the David Lewis Reentry Center are critical to getting people back up on their feet.

“EPA is one of the most in-need communities in San Mateo,” Morales said. “Essentially, the center is trying to provide people an array of social services based on what they need.”

Cabrera remembers trying to take advantage of everything when he participated. He did every type of counseling offered by the program: drug and substance abuse rehab, alcohol counseling, and therapy (he recalls how at first, it felt painfully awkward to hold a one-sided conversation until, well, he wound up liking it). He matched with a day job at a hazardous waste company and began to look for housing options to support his fledgling economic independence. He enrolled in vocational night classes, signing up for everything he could fit into his schedule, from computer typing (a highlight: “We’d play these typing games, and I got so competitive”) to resumé building to business fundamentals.

“I even joined classes for learning about the stock exchange,” Cabrera remembers, laughing. “When was I ever going to use any of that stuff, you know? But I did it anyway.”

This was Cabrera’s second round in the re-entry program. He tried in 2008, but didn’t stick with it — he went back to jail two months later on a parole violation. When he was released soon after, he found himself in his late 20s returning to the same house, same neighborhood, same friends, same gang disputes and drug deals, same threat of returning to jail. He wanted a change.

Cabrera has been incarcerated three times, the first for gang-related violence and the next two for parole violations. He explained that in EPA, like most anywhere else in the country, gangs are territorial about areas where they operate. What happened to him was simple and common enough: he was involved with one gang and got into a fight with members from another. It landed him in prison with a felony charge.

He declined to give names of either people or gangs involved: “That’s in my past,” he said. “Now I just want to build up the community I once helped destroy as a kid.”

In 2010, Cabrera graduated from the East Palo Alto re-entry program as part of the first class to complete the program after Lewis’ passing. The ceremony was, in part, a memorial for Lewis, a reminder that this work is never finished.

Cabrera took it to heart. His involvement with the re-entry program didn’t end then, as he often volunteered around EPA as a de-facto community ambassador for the center. Anything so he could give back.

If you visit the David Lewis Reentry Center today — now located on University Avenue, a few blocks past the “Welcome to East Palo Alto” sign greeting drivers entering from the 101 — you’ll see that years after the fact, Cabrera has indeed found a steady way to keep contributing to the local community. He’s been running the center since 2012.

* * *

[dropcap letter=”W”]hile he’s dedicated to his work, Cabrera is so much more than his job. In no particular order, here are a few things you learn about José Cabrera after a few minutes of conversation: he is a golf aficionado, a Girl Scout cookie connoisseur, and, if the bright “Frida Kahlo as Virgin Mary” print in his office is any indication, a casual collector of Chicanx art.

But what stands out immediately about Cabrera, before even saying a word, has nothing to do with his work or personal history. No, what you first notice, at least on this particular day, is his taste in music: Cabrera is Tejana singer Selena Quintanilla’s self-anointed number-one fan. He would have proudly told you himself, but he’s wearing an oversized baseball jersey with her classic signature embroidered across the front that already suggests as much.

“You’re a fan, too?” he’ll ask at one point, a smile playing across his face.

The gray jersey hangs loosely on Cabrera’s shoulders; “Corpus Christi – SELENA” stands out on his chest in bold black and red text. He’s still talking about Selena, may she rest in peace.

“Well, what number are you?” he continues, drawing rank. His serious tone is betrayed by a large grin. “‘Cause I’m number one, you know, so you’ve got to get in line.”

He’s casually thrown this jab in the middle of a conversation about county politics, mental illness, EPA crime and the effects of mass incarceration on marginalized and impoverished communities. This is Cabrera’s talent: an ability to seamlessly move between subject matter and make it accessible to whoever he’s talking to. You could be a local middle schooler, a recent parolee looking for future guidance, a county government financial officer, a Stanford professor or even a chatty reporter — he’ll still be able to get his message across, with an additional warmth and humanity that’s too often overlooked or missing in the American criminal justice system.

Under the mentorship of Robert Hoover, Lewis’ founding partner and then-director of the re-entry program, Cabrera began to consider applying for a position with the center, soon re-opening after a short hiatus following Lewis’ passing. Over long rounds on the golf course together, Hoover would teach Cabrera how to swing while encouraging him to channel his avid community engagement into a job at the center. In 2012, Cabrera interviewed — “I was nervous as hell,” he remembers — and was offered the position of case manager and, later, community worker, a role he retained after the program merged with the county.

Upon hearing his story, and hearing him tell it, it makes sense that Cabrera heads up the David Lewis Reentry Center. It makes sense because he talks about helping his community thrive with the same passion and enthusiasm with which he breaks down his favorite artist’s discography.

This gets to the heart of the matter, the motivation that drives the David Lewis Reentry Center and those who work with the program. The thing is, what Lewis realized — what Cabrera realizes, too — is that every number on every crime statistics report represents an actual living, breathing human being who has been transformed into a product of the American prison system. This is who they’re trying to help: people who are trying to start over, people who have very few other places to turn.

“These folks have trauma,” Cabrera said. “We think that no one will give you a shot or an opportunity or a chance. At least, that’s how I used to think.”

* * *

[dropcap letter=”M”]orales, the county’s interim correctional health services director, says that “it’s difficult to measure success” in the re-entry program.

“We try to look at a definition of recidivism,” Morales said. “The current definition is no incarcerations, or new convictions, for a period of three years.” He admits it’s a flawed criteria, but it’s what the county has to go by for now.

Both Cabrera and Morales are candid about the re-entry program’s limitations. To begin with, people need to be referred from jail or prison, and the resources they have access to depends on their eligibility as determined by Service Connect and various pieces of local and state legislation. For example, California Assembly Bill 109, described by the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as the “cornerstone of California’s solution to reduce overcrowding, costs and recidivism” in state prisons, enables nonviolent and nonsexual offenders to get earlier access to more services than other inmates.

Ensuring long-term effectiveness is also a challenge. Once someone completes their parole or probation time, the center lacks the capacity to keep tabs on them, and people are gradually cut off from various programming. Cabrera recalls an instance of a dedicated participant who made it off of parole and successfully graduated from the center. He remembers losing touch with him for a time — normal for former program participants — until he heard from mutual friends that the man had become re-addicted to heroin in the time since finishing the program. Cabrera reached out a few times, but there was virtually nothing he was authorized to do. For this man to regain full access to the center’s resources, he would have to re-offend and get another referral from jail or prison.

“If you’re not getting locked up, you’re doing good, but you have to be careful,” Cabrera said. “Once you get back on that lifestyle, it changes everything.”

Cabrera reports that 61 program participants will be awarded for their completion of the program at various stages following this Fall 2016 – Spring 2017 cycle. County representatives and probation and parole officers will attend the intimate awards ceremony.

Cabrera says this is usually a very emotional, proud moment for clients — a real achievement. For some of them, it will be one of the last times they come into the center. He wishes them the best.

* * *

[dropcap letter=”T”]he David Lewis Reentry Center is located in a cozy, refurbished house at the edge of East Palo Alto. In the backyard, which has mostly been turned into a parking lot, there are a few wild garden plots punctuated by a large sign leaning on the side fence greeting visitors as they enter and exit the lot. Centered on the canvas, in large, vibrant orange letters lined with deep blue, is the word “FAITH.” It’s impossible to miss; it’s everywhere: on the sign, through the doorway, and in the solidarity of the activists and professionals who support their community through this center.

In summing up his mission, Cabrera said, “I want to help everyone who was formerly incarcerated, you know, do what I can. I’m not going to leave my people behind.”

See also: Formerly incarcerated East Palo Alto re-entry center case manager is role model for clients