In response to reports of mismanagement, harassment and understaffing at Santa Clara’s Department of Family and Children’s Services, the county’s Child Abuse Council formed a committee on Oct. 14 to investigate the allegations.

The five-member committee will spend three months gathering existing information about social workers’ complaints by requesting access to employee exit interviews and internal investigations. The committee is also seeking permission to conduct an independent survey of current and former staff to determine the cause of discontent and generate solutions.

Out of 238 social worker positions at the county’s Department of Family and Children Services, 53 are currently unfilled. If the department cannot fill vacancies, slow the high employee turnover rate and keep people happy at work, council members worry that abused and neglected children will not get the help they need.

“Kids can get hurt, families — they can fall through the cracks,” said Ken Borelli, former deputy director of the Department of Family and Children’s Services and emeritus member of the Child Abuse Council, a body which acts as a watchdog for systems designed to protect children from abuse and neglect in Santa Clara County.

Department employee Jean D’Innocenti told the Child Abuse Council in September that social workers carry more than the standard number of cases, work excessive overtime and are unable to take more than two days of vacation without constant worry about their clients.

She also said that specific managers and supervisors have bullied employees to silence criticism and created an atmosphere of fear and intimidation that has led multiple people to resign.

“If we have social workers scared coming into the building and they are preoccupied with how they’re going to be treated that day, their focus is not going to be on the cases,” D’Innocenti said.

But department leadership says management might not be the problem. Rather, the rigorous nature of social work could be to blame. Social workers often experience extreme stress and vicarious trauma from the cases they manage.

“There are things that have gone on that have, in my language, hurt people,” deputy director of the Department of Family and Children’s Services, Jana Rickers, said at an Oct. 14 Child Abuse Council Meeting in response to the criticism. “What I’m not clear about is how much of that is something that management has done, and how much of it is part of the nature of the work in child welfare?”

The department has already taken a number of steps to address worker complaints, like holding “listening circles,” where employees can voice their concerns, conducting an exit survey to find out why people are leaving and making plans to relocate the call center to a space that is less cramped, according to Rickers.

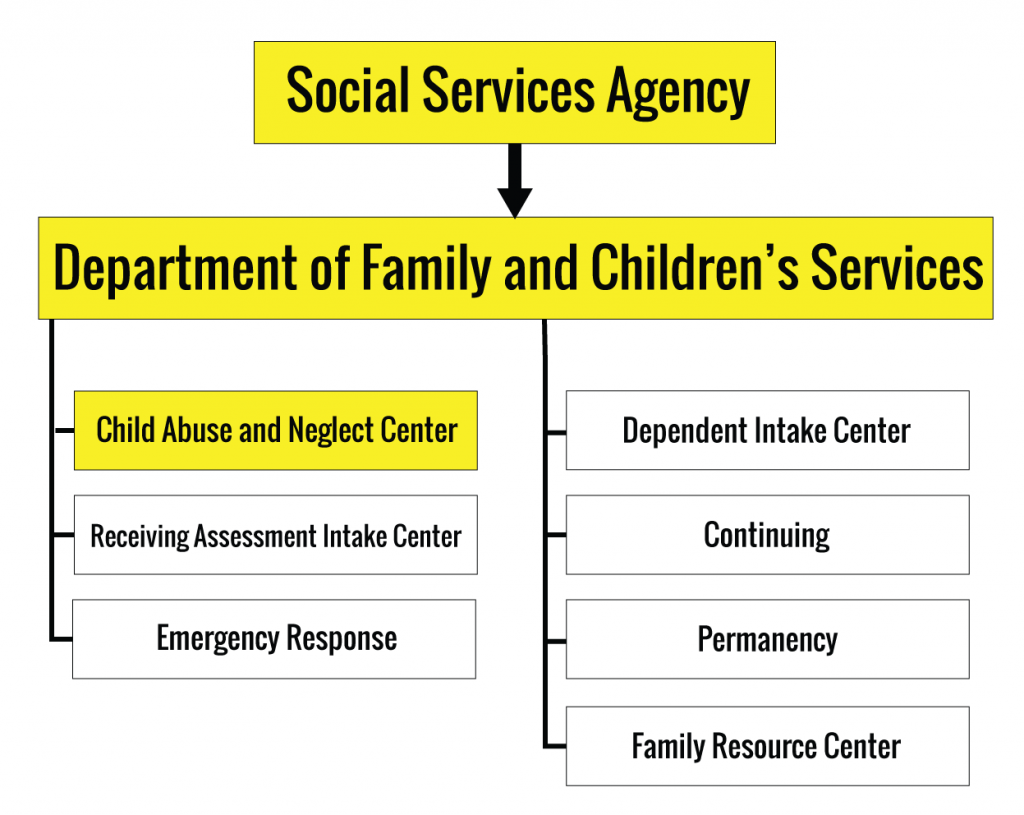

Dana McQuary, a manager at Santa Clara County Social Services Agency, which oversees the Department of Family and Children’s Services, said the department’s problems may be indicative of national trends.

“Child welfare agencies across the country are struggling with retention and recruitment,” McQuary wrote in an e-mail to Peninsula Press, when asked to comment on Santa Clara County’s performance in comparison to other counties. “The reasons for these difficulties appear to be related to the challenge of the field of social work (working with abuse and neglect on a daily basis), a shortage of qualified social workers and the lack of people pursuing social work as a career.”

While workers claim the issues are widespread throughout the department, many of the allegations are centered around its Child Abuse and Neglect Center. The center has a 24-hour hotline and social workers there act as the front line against child abuse, processing reports and determining the appropriate initial response.

According to an Oct. 6 Social Services Agency report, seven out of 25 positions at the call center are vacant.

A 2013 audit found that workers only answered about 59 percent of the calls, sparking criticism from county officials. Since then, the center has made improvements, and in August of this year, it reported answering 95 percent of calls.

But according to employees, the numbers are misleading because many calls are not being answered by trained social workers.

“The calls are answered by clerical workers getting their name and number to call back, and then responded to by us social workers when we get a chance,” Dawn Landshof, a single mother who has been employed by the county for 10 years, told the Peninsula Press. “But like I said, there are so many vacancies that there is hardly time.”

Landshof estimated that the center receives about 100 child abuse reports a day and that each call takes between 30 minutes and two hours to process. Data shows that between March and April, about 27 percent of calls were answered by clerical workers.

“But what if a child is being beat up?” Landshof wrote. “It only takes one call with a kid that needs help now, and then they are dead.”

Council Member Steve Baron said that having clerical workers answer some calls is not ideal, but it’s an improvement.

“It’s better than a person going to voicemail,” he said.

Baron volunteered to chair the committee that will investigate the Department of Family and Children’s Services.

“The bottom line from my concern is the protection of kids from abuse and neglect,” he said. “I do think the agency is moving in the right direction, but I think the light needs to continue to be shone, and there needs to be accountability to ask the hard questions.”