The surfer steps gingerly, one hand clinging to his board, the other pressed against jumbled rocks as he makes his way to the popular surf spot below. His suit blends into the dark crags, but his green board shines like a beacon. Swells smash against the steep rock face, spraying his ankles. He freezes at the water’s edge, timing his jump, uncertainty showing in the tense outline of his form.

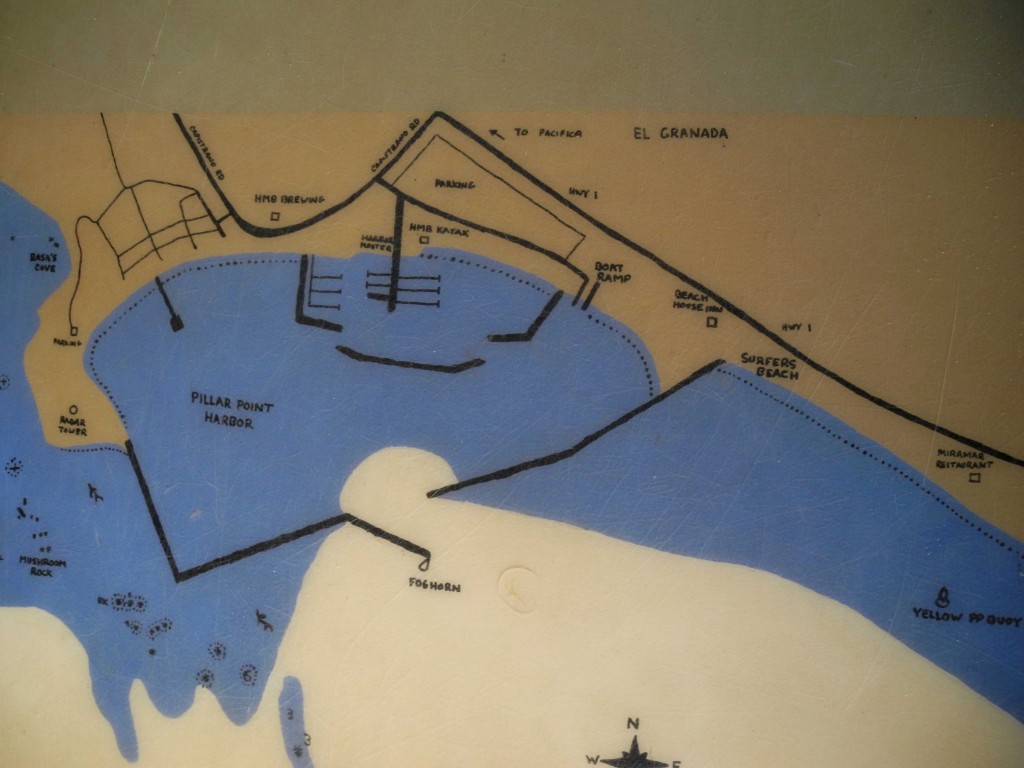

This climbing adventure is the only option these days for surfers hoping to ride the waves at a spot known as Surfer’s Beach, just south of Pillar Point Harbor near Half Moon Bay. In recent decades, the ocean has washed away the meadows and sandy beaches that once bordered the shore here. Now, a 12-foot cliff hugs the Pacific Coast Highway, and rocks have been dumped to protect the road. The only way to get to the surf is to climb down the boulders and jump straight into the water. The wide sandy beach where kids once frolicked is gone.

“Last year, my family could walk with a stroller down to the beach right there,” said Brian Overfelt, nodding toward the ocean barely separated from the highway by the riprap. Overfelt, 44, has lived in Princeton since he was two, and he fondly remembers a time when there was a broad expanse of land between the highway and the ocean. “There used to be a meadow there. There used to be a piece of land we called Turkey Overflow that was like a parking lot. It had a road to the beach. We would hang out there, we’d have lunch there, our moms would pick us up there, we’d have dates there, we’d take girls there, watch the sunset in there. Now the water is at the highway. It’s gone.”

Overfelt’s family owns and runs a restaurant and bar called Old Princeton Landing. Inside, ceiling beams hold a rainbow of surfboards, some signed by famous surfers who use them when they come to surf Mavericks, the famous big-wave break a mile to the west. Across from the neat stacks of liquor, locals chat with the bartender and each other about the weather. They discuss the unwelcome southerly winds and the height of the waves.

Overfelt arrives like a tropical storm moving toward hurricane status. His hands are waving, hugging, bumping fists. Blond curls shake with energy, flying around his head and directing his booming voice with help from his thick beard. Spit flies and his blue eyes blaze with energy.

He herds me towards the patio out back and jumps right in. “It’s a lot more serious than anyone realizes. Even the people that are totally proponents of it, they don’t realize how great it is. They don’t realize that it’s a win-win-win-win-win.”

He is talking about his big plan to save Surfer’s Beach, which he has been pursuing for over 10 years. Overfelt’s mother, Chris, and the bartender, Rusty, who sometimes serves as a judge on the Big Wave Tour, have already praised its genius to me. Overfelt’s plan is to dredge the sand building up inside Pillar Point Harbor, and move it to the sand-deficient Surfer’s Beach immediately to the south.

All along the coast of Northern California, the ocean flows from north to south and pushes the sand with it. This natural process creates big, sandy beaches and keeps the waves from creeping inland. When the flow of sand is disrupted — by a jetty, say, or a harbor — people can add sand to beaches manually in a process known as beach nourishment.

Pillar Point Harbor’s jetties have been blocking the southward flow of sand since 1965, and sand that would have blanketed Surfer’s Beach has been building up for decades inside the harbor, on the north side of the jetty.

Four creeks — St. Augustine, Dennison, Deer and one unnamed — contribute to the accumulation of sediment on the north side of the jetty by releasing their sandy water into the harbor. Deer Creek alone dumps over 3,000 tons of sand a year, according to a report by Robert Battalio, an ocean hydrologist from San Francisco. Heavy rains can increase the amount of sand flowing from the mountains and into the harbor by as much as eightfold. The mouth of Deer Creek deposits the weighty mass right next to the harbor’s primary boat launch.

“If you go to the breakwater and look over the wall, you’re going to see like 20-foot-high sand dunes,” Overfelt exclaimed. “Sand dunes! Inside the harbor! Deer Creek loads up that whole south wall of the breakwater. It’s just stuck in there.”

Overfelt blames the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary for preventing sand from the harbor to be used to nourish Surfer’s Beach: “I’m pissed at the sanctuary for doing that to this community. But they’re great. They do some great stuff. So I love them. But what the f***?”

I wanted to know why a sanctuary would prohibit Pillar Point Harbor from dredging, but the reason is surprisingly elusive, and I ran into the same complex web of unknowns and misdirection that has frustrated Overfelt for years. Many organizations — including the Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency, Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, San Mateo County Harbor District, California Coastal Commission and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — have a say in coastal development in Princeton.

In an attempt to understand the reasoning, I reached out to the Pillar Point Harbor and the local Half Moon Bay Review newspaper, both of whom directed me to the county harbor district. There, I hit a dead end. Assuming that officials at the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary would be able to explain their own regulations, I reached out to them only to find that the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary manages the northern portion of the Monterey Sanctuary.

“When the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary was created in 1992, they created a designation document that depicted how the sanctuary was to be managed,” explained Max Delaney, permit coordinator for the Farallones sanctuary. “This was back in an era when there was concern about having a bunch of contaminated sand in the harbor. You might have boats and industries in the harbor area leaking contamination that builds up in the mud. It didn’t seem like a compatible area to include in the marine sanctuary.”

The dredging restrictions were created to protect the local coastal environment from contaminated sand and sediment. To avoid endangering the marine life, the sanctuary’s regulations dictate that sediment from the harbor must be disposed at designated dumping sites, which means it can’t be transported to the adjacent beach just south of the jetty — a solution that Overfelt regards as simpler, cheaper, smarter and essential.

“Here’s what’s crazy,” Overfelt says, his excitement growing and his body almost rumbling. “They dredge every harbor in America but ours. Let me say that one more time. They do it in every harbor. And here’s the thing. We’re in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary with three other harbors: Monterey, Moss Landing and Santa Cruz. They dredge all three!”

Overfelt himself spearheaded an effort to prove that the sediment in Pillar Point Harbor is clean. When he was told the sand would be full of clay, silt and toxins, he followed the instructions of his friend Ryan Seelbach, a geologist and Maverick’s surfer from San Francisco. Digging five feet down in four different spots of the harbor during a negative tide, Overfelt produced two bucketfuls worth of sand for Seelbach to test.

Smug with victory, Overfelt revealed, “He calls me after a week and goes, ‘Dude! You were right!’ He goes, ‘That f****** sand is like white, beautiful granite sand.’” Overfelt is convinced that if that sand were placed on Surfer’s Beach every few years, it would replenish the beach and make it accessible once again for locals and tourists alike. The sand would continue migrating south to further nourish Miramar, Roosevelt, Dunes and Venice Beaches.

Delaney, of the Farallones Sanctuary, agrees: “At Pillar Point you can definitely see the advantage of doing beach nourishment,” he said. “We actually have a bunch of sand that is clean. But the language is difficult to change.”

Five weeks after my visit with Overfelt, he learned that his years of hard work were starting to pay off. At a March 9 meeting, in a partial victory for Overfelt, representatives from Princeton Harbor’s many stakeholders agreed to begin taking steps to replenish the sand at Surfer’s Beach.

A grant of $800,000 will be used to lace 75,000 cubic yards of sand along Surfer’s Beach and to the south. The sand will come from approved upland sources or quarries and can be dumped on the riprap and placed right at the foot of the cliffs. From there, it will be spread out by the ocean to slowly recreate sloping beaches.

One day, Overfelt would like to see the sand coming from inside the harbor, but for now that sand will have to go to designated dredge disposal sites. These areas are places in the sanctuary where negative impacts from contamination would be limited because of their distance from shore or their low biodiversity. If dredged material stays in the sanctuary, it has to be disposed of in one of these locations.

No sand, even from an inland location, can be placed in the sanctuary surrounding Pillar Point as the regulations currently stand. The sanctuary border is at the mean high tide mark, which explains why the new sand will be placed above this line and then slowly be washed into the sanctuary.

“The plan will definitely still slow down the erosion and help Surfer’s Beach,” Delaney said. “But if more beach nourishment projects are proposed, the best way to go about it is to put sand both above and below the high tide mark. In the future, the sanctuary will have to consider changing what our definition of disposal is or changing the language of the sanctuary documentation.”

Nourishing the beach will benefit the region in many ways, Overfelt says. He cites the importance of having beaches and good waves to boost the town’s tourism industry. More than 2.5 million people visit Princeton annually – which is thousands of times larger than the population itself. Additionally, beaches to the south of Princeton are suffering from the absence of sand being held captive in the harbor. The snowy plover, a threatened bird that lives on sandy beaches about two miles south, is quickly losing habitat. A multitude of well-researched reasons demonstrate the importance of Overfelt’s success, but his heart is really in recreating the home that he once knew.

“I’m so passionate about this ‘cause I want to surf out there like it was,” he says. “I want to protect the highway and the birds, I want my daughter to surf out there like it was. I want the visitors and people who come down to go, ‘F*** this place is rad.’

“This is how I know I’m right. If you take away the breakwater, if you go back to 1850, what was there? There were four creeks running out of these mountains bringing sand and nourishing our beaches. If you go back to the way it was before man messed it up, it’s unbelievable. That is where you start. You start with what was natural and what was here before, and you go from there.”