Twenty years ago, Elizabeth Huerta saw opportunity in the Central Valley’s vast green fields when she and her family migrated from Michoacán, Mexico to find farm work. She’s worked pruning tomatoes, shaking almond trees and digging up garlic for the past 15 years. Sometimes she runs into her husband who waters pistachio and almond trees.

But in the recent months, as California’s drought has worsened, Huerta’s family — like others — have considered returning to Mexico.

“With no water, they can’t harvest the fields,” Huerta said. “And without a harvest, there is just no work anymore.”

Huerta, her husband, and two of their four children live in a small apartment in Huron, a small town 50 miles south of Fresno. When they turn on the kitchen faucet, light brown water pours out. On Saturday mornings, then, Huerta buys the cheapest bottled water she can find for the week’s drinking and cooking. When her husband has less hours of work, she visits her daughter about 25 minutes away to fill up a plastic bucket with about four gallons of water to get by.

[columns_row width=”half”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

Elizabeth Huerta shows a photo of her grandson. (Carolina Wilson/Peninsula Press)

As California’s water crisis looms over the agricultural industry, conversations have focused on the threat to big growers while often overlooking the devastating potential impact to the laborers and small migrant communities.

Agricultural laborers face not only work shortages but also the increased potential of contaminated water supplies. This threatens both their health and their economic stability, as a disproportionate amount of their budgets is spent on private water supplies and other basic needs.

But, basic needs cannot be purchased if members of the community are unemployed — a fear that’s become more and more of a reality for farmworkers battling the drought — in the fields and at home.

In the fields

It’s 4:30 a.m. on a Thursday morning and about 20 laborers are waiting outside the only Chevron gas station in Huron. One truck pulls up to pick up workers. The truck fits six.

[columns_row width=”half”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

Farmworkers wait outside of a Huron gas station waiting for trucks to take them to fields for work. (Carolina Wilson/Peninsula Press)

The other workers wait for another half hour. In traditional fieldwork attire, only their hands and faces are uncovered. There’s no idle chat this morning; the workers just wait in silence. After another half hour, with no more signs of farm trucks seeking employees for the day, the workers return home. Leaving in pairs of two, they hope for more luck the next morning.

Thomas Esqueda, director of public utilities for the City of Fresno, said there have been several farmers that have indicated they cannot farm their land this year due to the drought.

“So no pruning, no picking and no cultivation is going on,” Esqueda said. “People are jobless as a result of not having water available.”

With little to no work opportunities found locally, many migrant families find themselves having to travel to find work.

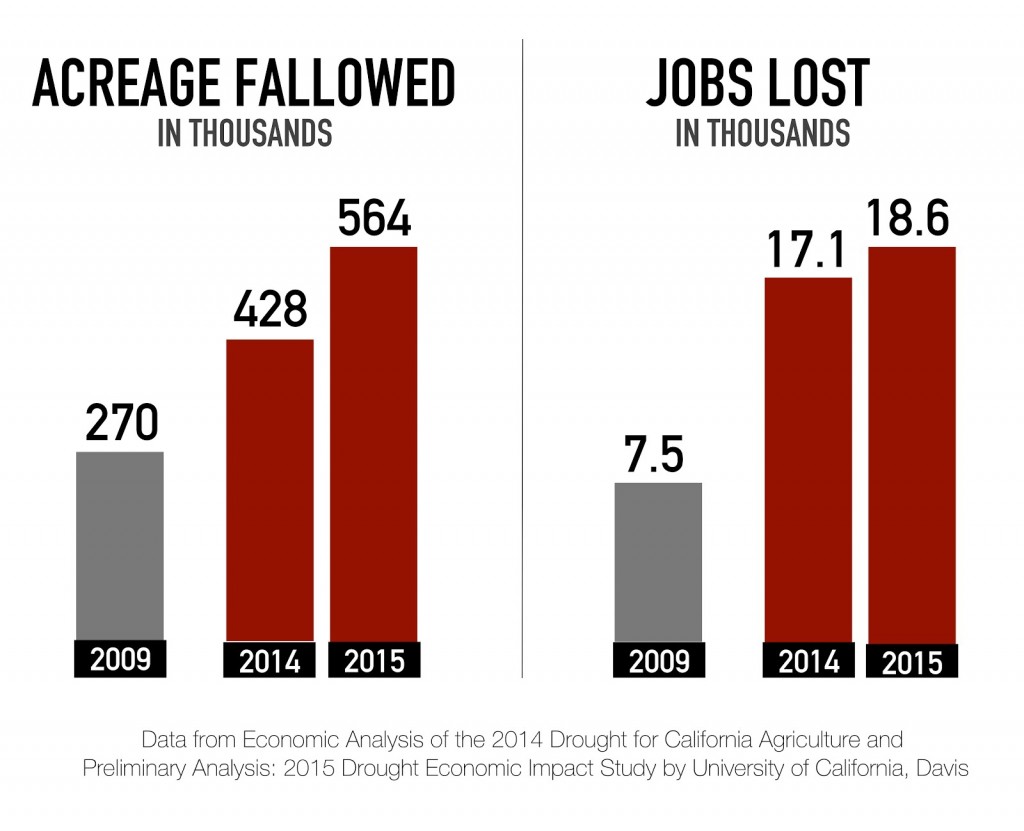

An estimated 17,100 seasonal and part-time jobs were lost in 2014, according to researchers at the University of California-Davis who studied the drought’s economic impact.

Blueberries are harvested on a farm in Fresno County. (Carolina Wilson/Peninsula Press)

There was also a 6.6 million acre-foot reduction in service water available to agriculture.

“The 2014 drought is responsible for the greatest absolute reduction in water availability for California agriculture ever seen,” the report stated, estimating that 428,000 acres fallowed in 2014. Approximately 60 percent of that fallowed cropland occurred in the San Joaquin Valley.

Studies by the University of California, Davis on the effect of the drought on the state of California.

Another Huron resident, Martha Moreno, travels seven hours south to Brawley, California, for farm work, a city that is less than one hour from the California-Mexico border.

Workers like Moreno, then, find themselves away from home for three-to-four weeks at a time, adding hotel, food and babysitting costs to an already overwhelming list of expenses.

“It’s a real battle because I already have four kids that depend on me,” Moreno said. “The drought doesn’t only affect work, but it also affects our families, because many times we have to leave our children with strangers.”

The Community Water Center (CWC), headquartered in Visalia, California, is another organization that helps communities — like the small town of Seville — in the Central and San Joaquin Valleys advocate for water rights.

The majority of residents in Seville are farmworkers, with a median household income of about $14,000 a year. Stone Corral Elementary in Seville — the poorest school in California — was forced to spend about $500 a month on bottled water. After 50 years without access to safe drinking water, the CWC helped the small town of Seville get a new well in fall of 2014.

“These areas have some of the highest poverty rates in the country,” Jenny Rempel of the CWC said. “With agricultural areas being fallowed, that’s higher unemployment rates and rising lines in terms of food assistance.”

Rempel believes that although the drought is an emergency, it’s also an opportunity to leverage the attention the state has on these communities.

Seen in the Central Valley. (Carolina Wilson/Peninsula Press)

More specifically, the CWC supports policy to ensure access to affordable drinking water. AB 401, for example, would require the Department of Community Services and Development to develop a plan for a Low Income Water Rate Assistance program by 2017.

“We need to think about putting systems in place that redistribute power, so that all residents can have a voice in the policies that are impacting their quality of life, especially at home.”

At home

“But, why worry about securing work when I’m even more scared to drink my water at home?” Huerta asks.

According to the CWC, over one million Californians don’t have access to clean drinking water. Rempel says it’s likely that as the drought drives excessive drilling for water, water tables will drop and contamination rates will rise. The lower the water table is, the more likely it is that chemical contaminates be present.

“In California, in 2015, there are over 350 small communities that on a recurring basis lack safe water,” Rempel said.

The source of the information is the Division of Drinking Water’s database known as SDWIS. Only small PWS (<3300 service connections or <10,000 population), as defined by Health and Safety code section 116275(aa) and those owned by entities other than the federal government or state government are included. Only PWS with either an exceedance of Chrome VI MCL in monitoring conducted since July 1, 2014, or violation(s) of safe drinking water standards in at least one source in 2014 as follows: at least one MCL violation (for arsenic, nitrate, radioactivity, THMs, etc), or at least one treatment violation, or at least one Total Coliform Rule (pathogen) violation.

One of those small communities is Lost Hills, a Central Valley community with a population of just about 2,000 people.

Rosanna Esparza of the Clean Water Fund works closely with this Kern County community and said its residents know something is wrong with their water because they can see it and smell it.

According to California’s Water Boards’ data, in fact, about 1 in 4 people in Kern County are affected by a contaminated public water system.

“For most of us, water is an entity that can flow freely, but when you describe it as a thick, clump coming out of your faucet, you have another dimension to water that most people don’t understand or recognize,” Esparza said.

And so contaminated drinking water exacerbates the pressure farmworking communities endure during the drought. Both Huerta and Moreno have seriously considered returning their families to Mexico.

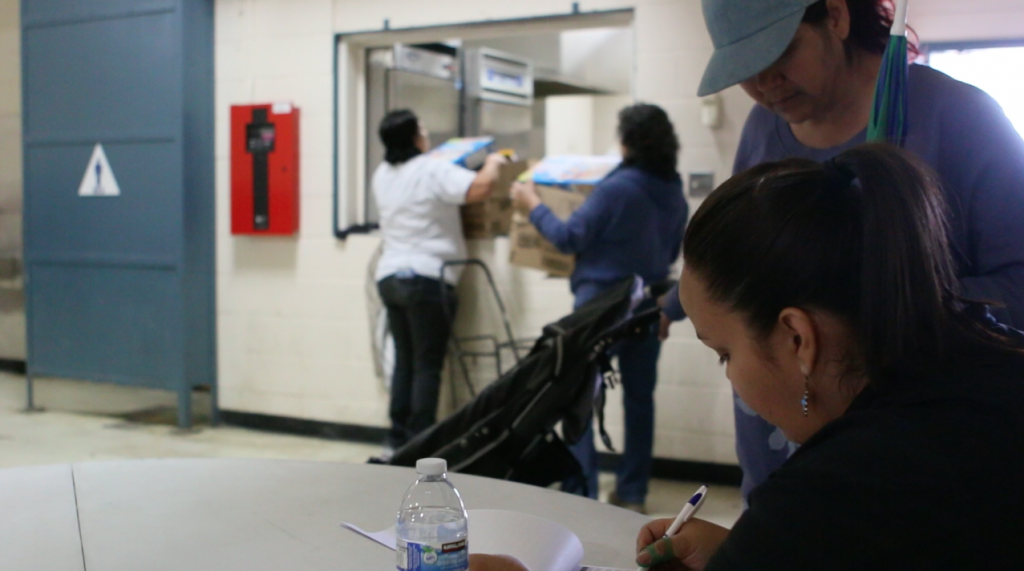

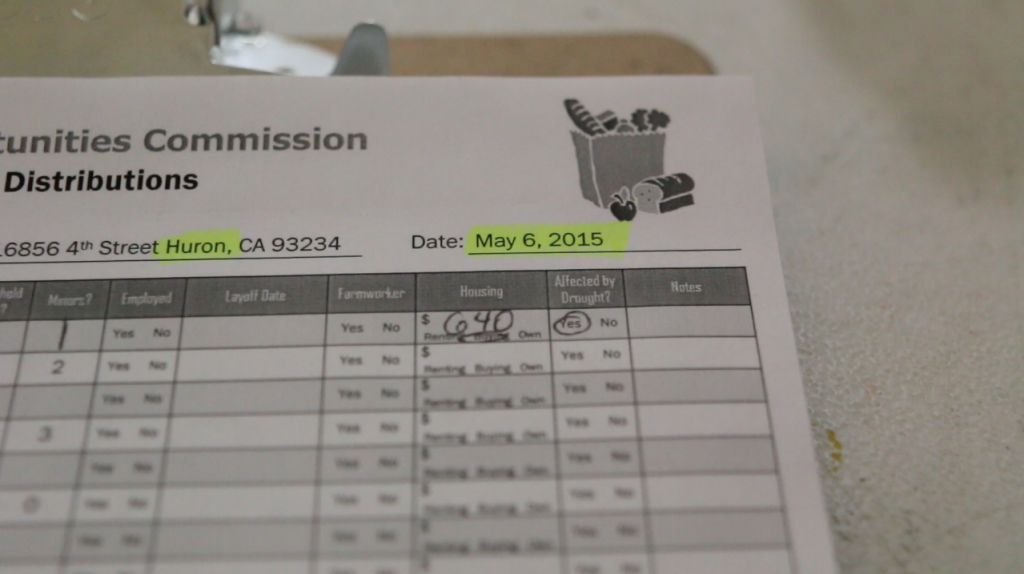

For now, Moreno just finds herself returning almost every Thursday to John Palacios Community Center about two blocks from her house. Several dozens of Huron residents form lines to pick up bags of bread and cereal from food assistance programs — lines that have gotten longer as more people have lost their jobs in the fields.

Before picking up food, residents are asked several questions in the form of a questionnaire. Names, addresses and ages varied. But when asked if they felt their lives were affected by the drought, the answer remained the same.

“From what we hear, it’s just going to get more and more difficult,” Moreno said. “I’m worried for what’s to come.”

[columns_row width=”half”]

[column]

[/column]

[column]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

Huron residents form food assistance lines at John Palacios Community Center, where they are surveyed about the effect of the drought on their homes. (Carolina Wilson/Peninsula Press)

This in-depth story was reported and produced by Carolina Wilson (Stanford Journalism MA ’15) as a master’s project, which was advised by Stanford Hearst Professional in Residence Dan Nguyen.