Almost 12 million people saw Brittany Maynard’s final days battling terminal brain cancer in a video requesting the right to die. In November 2014, Maynard, 29, chose to end her life after moving to Oregon to take advantage of the state’s aid-in-dying law.

It was not Maynard or her family who widely shared the video that attracted national attention to the issue of aid-in-dying legislation. Maynard reached out to Compassion & Choices, said Toni Broaddus, California campaign director for the organization. The nonprofit is dedicated to passing aid-in-dying legislation in California and nationally, and promoted Maynard’s video, organized primetime interviews, perpetuated a national conversation and continued to share her story after her death.

Compassion & Choices and other such organizations have taken advantage of the latest digital technologies to bolster the conversation about the right to die.

“It’s clear that social media is the reason this issue has gained so much momentum so quickly because it is now possible for a story like Brittany’s to go global in just a matter of hours,” Broaddus said.

The latest campaign effort in the United States surrounding the aid-in-dying conversation was centered on a piece of legislation in California, Maynard’s home state, which the state assembly passed on Sept. 11 after a months-long effort. Now, the legislation awaits final approval by the Senate, which passed it initially last spring. From there, it will go to Gov. Jerry Brown.

Funding data for the legislative effort has been limited, but one thing is clear: nonprofit organizations were coordinating campaign efforts to market the conversation for and against the right to die. Organizations such as Compassion & Choices and Death with Dignity led the effort through educating and rallying the public to press legislators to pass Senate Bill 128. On the con side, organizations such as National Right to Life and the Disability Rights and Education Fund have voiced concerns in media and in legislative hearings over potential abuse of disabled and elderly patients and family members through the legalization of aid-in-dying.

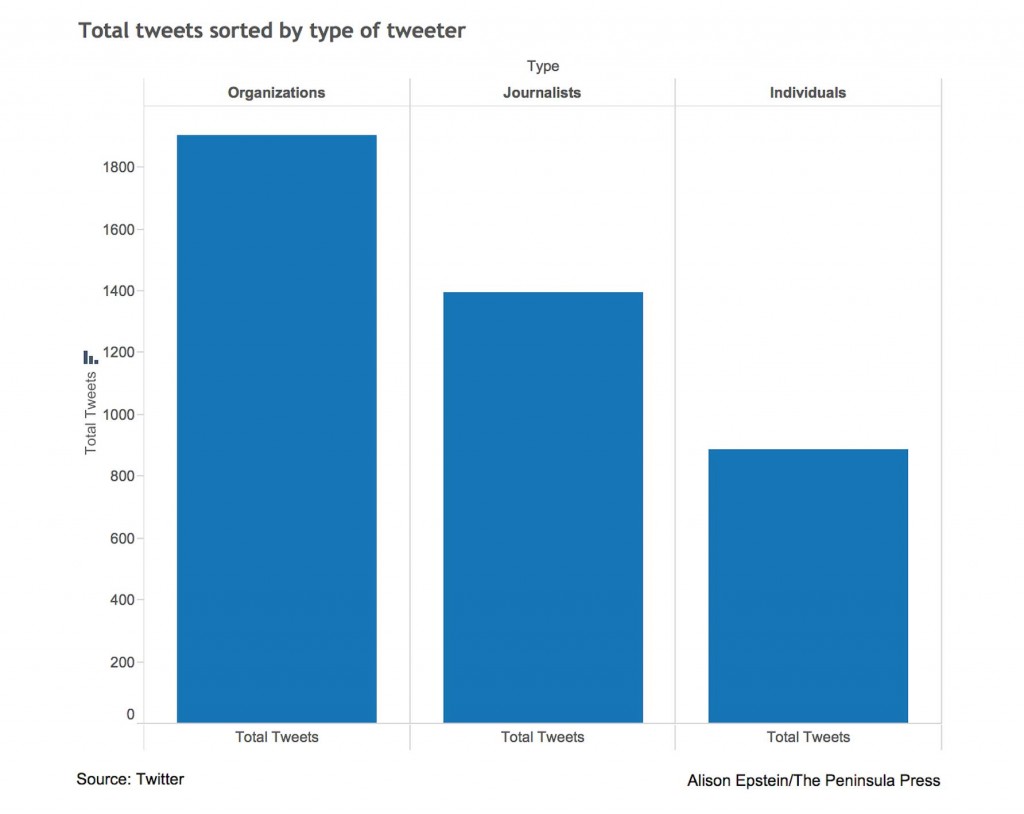

A team of Peninsula Press reporters at Stanford analyzed more than 25,000 tweets from April and May 2015 generated by nonprofit organizations, journalists and high-profile individuals around the world. The analysis found that, both nationally and internationally, it’s established organizations that are most successful at generating retweets and consequently drawing more people into the right-to-die conversation.

The Peninsula Press team also collected funding data for electoral campaigns on aid-in-dying legislation for 2008 and 2012, in Oregon and Massachusetts respectively. The data revealed national organizations are the leading contributors to these legislative efforts.

National conversation on the right to die decades in the making

[dropcap letter=”T”]he conversation around the right to die in the United States began decades ago in Oregon, the state to where Maynard was forced to move in order to take advantage of existing aid-in-dying laws.

In 1994, Oregon voters, by a margin of 51-49 percent approved a Death With Dignity Act ballot initiative that would grant terminally ill patients the ability to request lethal medication. This initiative became law in 1997, allowing “mentally competent, terminally ill adult state residents to voluntarily request and receive a prescription medication to hasten their death,” according to the Death With Dignity National Center.

More than a decade later, in 2007, California — Maynard’s home state — considered its first right to die legislation. The legislation, however, was shut down. Some of the pushback came from arguments by religious groups who suggested that suicide is an immoral act. Others expressed concern that under such a law, relatives might pressure the sick into accepting the lethal medication, and that insurance companies might abuse the law.

Washington state’s Death With Dignity Act went into effect on March 5, 2009, and Vermont followed on May 20, 2013. After 2007, according to the Death With Dignity National Center, legislators in California did not seriously consider passing a right to die law — until Maynard.

In April of 2014, Maynard was diagnosed with grade 4 astrocytoma, a brain tumor. Doctors gave her six months to live. Maynard moved from California to Oregon, where she would have a choice over how long she lived.

“That’s the strength of the legislation,” said Dan Diaz, Maynard’s widower in an interview in the spring. “It’s up to the individual. There is no timeline, there is no requirement in that regard. The person who is terminally ill lives as long as they possibly can. I mean, that’s always the goal”

After battling worsening seizures and other pain, Maynard chose to die on Nov. 1, 2014 in Oregon surrounded by friends and family.

“Goodbye to all my dear friends and family that I love,” wrote Maynard in her final Facebook post. “Today is the day I have chosen to pass away with dignity in the face of my terminal illness, this terrible brain cancer that has taken so much from me … but would have taken so much more.”

In California, nonprofits invest in educating the public

[dropcap letter=”S”]enators Bill Monning and Lois Wolk, SB 128’s sponsors, approached Compassion & Choices regarding the bill shortly after Maynard’s death in November of last year. The senators officially introduced the bill in January 2015.

The nonprofit was caught slightly off-guard when the senators first approached them; it marked the first time that legislators reached out to the nonprofit and not the other way around. Compassion & Choices was not planning to go to the Legislature during 2015, Broaddus said. The nonprofit, however, was ready to seize the opportunity the senators presented them.

The nonprofit, Broaddus said, had been involved in different attempts to pass aid-in-dying legislation in California. But after the failure to pass such legislation in 2007, the organization pulled away from the state to re-strategize and raise funding for a revised campaign.

“California is always in any social justice campaign. It’s always a really important state,” Broaddus said. “It tends to be one of the early adopters of social justice policies that make people’s lives better, so there was always an attempt and understanding that we had to do something big in California.”

In 2013, the group reinvested its national resources into the state, mainly focusing on educating the public about end-of-life options; political action was then an uncertainty. That focus on public education and discourse has been key, said Jennifer Glass in the spring, just months before her death of Stage 4 lung cancer. Glass, was a San Mateo resident who collaborated with Compassion & Choices to garner support for the legislation. Glass was diagnosed with a terminal cancer in 2013 and died in August, just a few weeks before the assembly passed the bill.

In the spring, Glass said that efforts to pass aid-in-dying legislation in the past largely faltered due to social taboo over openly discussing such an issue.

“The biggest impediment historically, I believe, has been people’s fear of the conversation,” Glass said at the time.

But last year, with the appearance of Maynard’s story, followed by the sudden support of Monning and Wolk, Compassion & Choices found itself in a position to once again campaign for aid-in-dying legislation in California.

Beginning last November, the organization trained over 853 volunteers in California for the legislative effort, Broaddus said. Volunteers went to local markets and rotary clubs, talked to people about end of life options and urged voters to contact their legislators regarding passage of the bill. The organization also has offered terminally ill patients and their families end-of-life counseling services and has a legal team on hand to help terminally ill patients.

For its part, the Oregon-based Death with Dignity National Center also invested resources in arranging speaking events in California with the goal of explaining end-of-life options, said George Eighmey, vice president of the organization.

Compassion and Choices has also funded four different lobbying firms to help the bill move along.

“We’re investing a lot of financial resources into the people that we need to help make this bill move forward and make a change,” Broaddus said in an interview in the spring.

Broaddus could not provide an estimate of how much funding has gone towards the lobbying firms.

Diaz said that organizations with established resources and know-how like Compassion & Choices are key to bringing thousands of individual stories to public attention. Diaz can’t precisely say that his wife’s widely shared video would have garnered that much attention without the publicity provided by Compassion & Choices, but he credits the nonprofit’s influence.

“I guess it may have gotten a lot of initial attention but then maybe tapered off a bit more,” Diaz said in the spring. “Whereas because of Compassion & Choices and the media-savvy that they have, they’ve been able to keep it, kind of the focus on it, and also utilize it at the appropriate times with legislators.”

Months after his wife’s passing, Diaz continued to collaborate with Compassion & Choices. He participated in speaking engagements and reached out to legislators, all the while sharing his family’s story. For Diaz, it was a matter of personal advocacy. It also was a means by which he could keep his promise to his wife to work to get aid-in-dying legislation passed at least in their home state of California.

“It’s personal. That’s the promise I made to Brittany,” Diaz said.

What the opposition says

[dropcap letter=”O”]rganizations such as Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund have spoken out against the passage of SB 128. DREDF had warned against the potential abuse of an aid-in-dying law, spreading its message through social media efforts, through articles in the media, and through educating California legislators on their position, said Senior Policy Analyst Marilyn Golden earlier this spring.

Golden said in a spring interview that there have never been safeguards put into place to prevent abuse of aid-in-dying, especially relating to the elderly and the disabled. In Oregon, she added, there is no investigation of abuse and no way to report abuse. Oregon does not show abuse because the system is set up not to find it.

“Where assisted suicide is legal, an heir or an abusive caregiver may steer the person toward assisted suicide, illegally witness their request, pick up the lethal dose for the ill person, and in the end they can even administer it, because no objective witnesses are required at the death,” Golden said.

Golden also commented on situations such as “doctor shopping” where families shop around for doctors until they find one willing to assist in an individual’s premature death, and misdiagnosis, that is a common occurrence in medicine, where an original diagnosis ends up changing with time, Golden said. If a person is misdiagnosed as terminally ill in a state where aid-in-dying is legal, this person may take advantage of the aid-in-dying law and miss out on potential treatments and good years of their life, Golden said.

“I object to calling this the right to die,” Golden said. “Our opposition is about the fact that where it’s legal the Oregon model puts many people at dangerous risk of harm. Other people may call it a particular thing, we call it assisted suicide because that’s the name they use in medical and in legal professions.”

Diaz, in addressing those who opposed the legislation, had one question.

“How would they suggest that my wife die?” Diaz asked.

Golden spoke of one alternative to aid-in-dying, a form of sedation called “palliative sedation” where the suffering patient is sedated to a point of comfort while the dying process takes place.

“For people who are experiencing a painful death who could not be relieved otherwise,” said Golden, “it is legal in every state to get palliative sedation. That should not be dismissed as an alternative. We already have a solution that doesn’t endanger people in the way the assisted suicide law would.”

Glass used palliative sedation in her final days, according to a report on the Compassion & Choices website. Her husband, Harlan Seymour, in that report, criticized the method as inadequate.

“Jennifer underwent palliative sedation because her symptoms had become unbearable. She was unable to breathe and in enormous pain. Unfortunately, she was not able to take advantage of the end-of-life option — medical aid in dying — that she gave her precious time to make available,” Seymour was quoted by Compassion & Choices.

The bill moved forward with support from nonprofits

[dropcap letter=”T”]he path to the Assembly passing the legislation on Sept. 11 was full of stops and starts. The bill passed the Senate Health Committee in March and the Senate Judiciary Committee in April. Then the Senate Appropriations Committee suspended the vote, putting the bill at risk to be killed in the committee. Eventually, the legislation passed to the Senate floor and then on June 4, the Senate passed it.

One of the key shifts in the legislation’s likelihood for success came after the California Medical Association (CMA), a historic opponent to aid-in-dying legislation stated on May 20, that it was neutral on the passage of the legislation.

“The decision to participate in the End of Life Option Act is a very personal one between a doctor and their patient,” said CMA President Luther F. Cobb in a press release on the subject. “Which is why CMA has removed policy that outright objects to physicians aiding terminally ill patients in end of life options.”

“Their position of neutrality allows I think for senators to recognize that it’s OK for this bill from an ethical standpoint, a moral standpoint, a logical standpoint to move forward,” Diaz said in the spring.

But then early in the summer, the bill didn’t make it out of an Assembly health committee. At the time, news reports suggested the legislation would not be considered again until the next regular legislative session. In August, after Gov. Brown called a special session on healthcare spending, the bill was reintroduced.

The governor’s office had suggested that the special session was not the time to revisit the legislation and he has given little public indication of how he plans to deal with it, but Eighmey of Death with Dignity said in the spring that he was “cautiously optimistic that the governor will sign it.”

“He has made comments in the past that would indicate he would be willing to pass this option as long as you ensure that individuals who are vulnerable don’t take advantage of it,” Eighmey said.

CORRECTION – Editor’s Note (9/15/2015): In this story originally published Sept. 14, 2015, Peninsula Press had misspelled Harlan Seymour’s name. The name appears corrected in the story above.