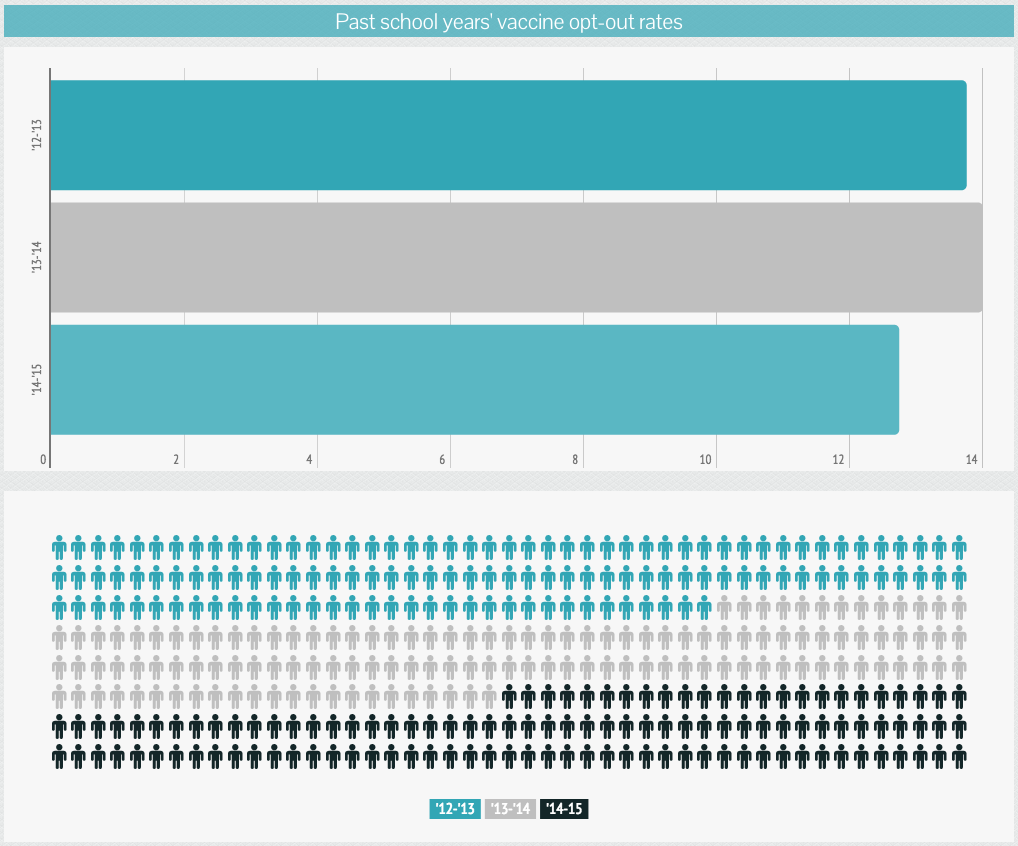

The number of students opting out of vaccinations because of a “personal belief exemption,” has decreased in California by 8 percent from the 2013-2014 school year to the 2014-2015 school year.

The drop is an especially welcome change to Cathy Owens, the coordinator of health services for Vista Murrieta High School in Riverside, Calif., which experienced a measles outbreak at the end of 2014.

Starting in January 2014, parents have been required to meet with a doctor or a certified health practitioner if they wanted to opt out of their kids’ vaccinations, Owens said.

“I think having to discuss it with a health professional put pressure on parents to vaccinate their kids, because they realized what kind of risk they were putting on the rest of the students,” Owens said.

Although opt-outs have decreased in the last year, California State Senators Richard Pan (D) and Ben Allen (D) are attempting to remove them altogether in a new bill, which would fully remove personal belief exemptions from the existing law. Students can still opt out for medical reasons.

“We have substantial policy on record supporting this type of good public policy because it helps to keep individual children, schools and communities healthier and safe,” the California Medical Association said in a statement. “SB 277 is a step in the right direction for the health and safety of the public to ensure that unnecessary outbreaks of once eradicated diseases don’t resurface.”

The change in legislation alongside the decrease in personal belief exemptions is significant but not surprising, said Harvey Kaslow, professor of physiology and biophysics at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“After enough people see enough cases of [measles and other diseases] then the risk-benefit ratio will shift,” Kaslow said.

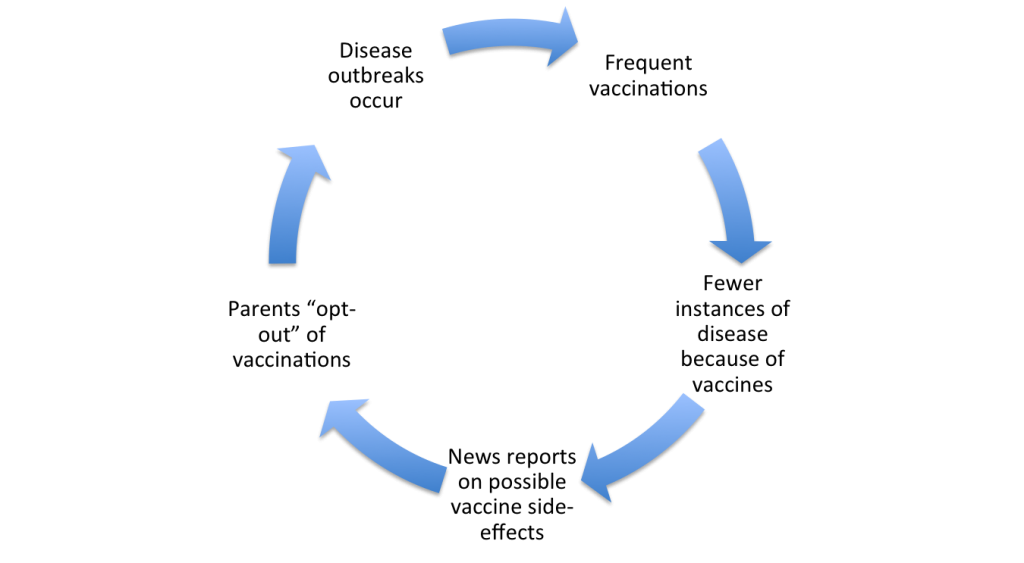

From Kaslow’s experience studying the relationship between diseases and vaccines — particularly pertussis (whooping cough) — higher vaccination rates as a response to outbreaks is not a new phenomenon.

“It’s a cycle,” Kaslow said. “Diseases pose a big threat; people start vaccinating their kids; and the vaccines do a great job diminishing the incidents of the disease. News reports potential side effects of vaccines now start floating around and so people then create their own risk-benefit ratio that is not at all based on facts or science.”

Megan Sandlin, a mother of two, started as a believer in the anti-vaccination movement. As a young mother, she liked the ideal of an organic lifestyle, she said.

“I entered a world full of cloth diapers, ‘intactivism,’ and home birth,” Sandlin said. “I made a lot of new friends who shared my beliefs about peaceful attachment parenting, and I started to notice a trend — many of these same friends also didn’t vaccinate.”

Sandlin began looking up the ingredients in vaccines and said she saw some “nasty-sounding” chemicals. Although many government-sponsored research and health websites explained the benefits to vaccines, Sandlin’s anti-vaccination friends explained that this information was unreliable — and Sandlin believed them.

However, as the young mother was exposed to more news over time, she realized a lot of the information she had learned from her friends was untrue, and she began to change her belief system about vaccines.

It’s hard to believe now how easily I bought into everything I was hearing from the anti-vaccine crowd.

“In the end, I couldn’t continue to deny the science. It’s hard to believe now how easily I bought into everything I was hearing from the anti-vaccine crowd,” Sandlin said. “It seems extremely obvious now.”

The change in heart Sandlin and others like her experienced does not account for the opt-out rates of all California counties: 13 of the 57 counties in California saw an increase in opt-outs for the 2014-2015 school year.