A vote on whether to limit the amount of office space that can be added to Menlo Park is pitting neighbor against neighbor and shaping up to be the most divisive issue in the upcoming city council election.

As Nov. 4 nears, money is pouring into campaigns for and against the citywide Measure M in one of the hottest real estate markets in the country, especially since Facebook moved here in 2011. Measure M — more than simply a yes or no on potential development – is being portrayed as a vote on the future identity of Menlo Park.

At issue is whether to retain the small-town character that some residents say is disappearing, or to follow the lead of neighboring cities such as Redwood City, which are building large-scale infrastructure to attract tech jobs and tax revenue.

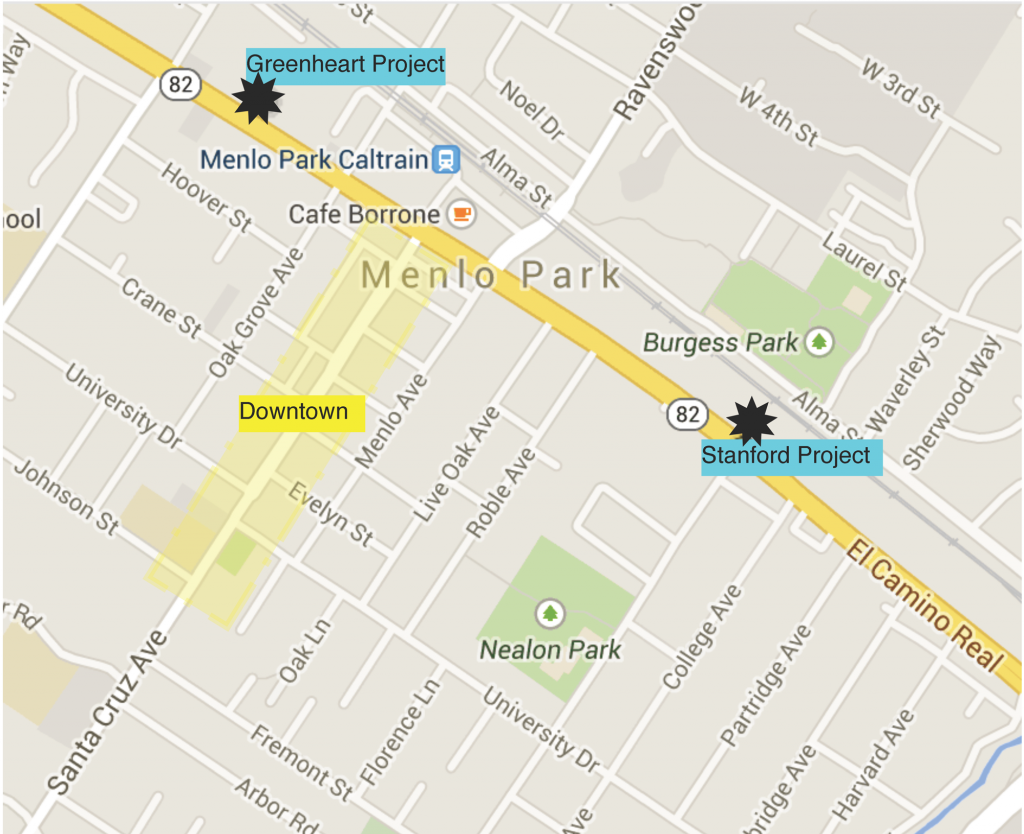

Measure M would limit the amount of future office space allowed downtown and along El Camino Real to no more than 100,000 square feet per project, and would require citywide elections to exceed this cap. If approved by voters, Measure M would delay or halt two large development projects under review by the city.

Stanford University and Greenheart Land Company are proposing to build up to 409,500 square feet of offices — the size of seven football fields — in addition to 390 apartments and retail space. Both developers said that if Measure M passes, they would scrap their projects and begin anew or not continue at all.

(Editor’s note: Peninsula Press is a project of the Stanford Journalism Program at Stanford University.)

The group behind the initiative, Save Menlo, raised over $48,300 in small donations from dozens of residents, many of them retired. They say passing the measure would prevent an increase in peak-hour traffic and steer the city towards other types of developments desired by the community, such as hotels, cafes and open-air plazas. The city council and other opponents say Measure M would upend a multi-year planning process by the local government to end blight and revitalize the area, and it would deprive the city of millions in revenue.

A group battling Measure M, Menlo Park Deserves Better, raised over $7,500. Greenheart Land Company, which says it could face a two-year delay on its project and lose millions of dollars if Measure M passes, donated $200,000 to the Committee for a Vibrant Downtown, which is fighting the measure through fliers, phone banking and signs.

The Stanford and Greenheart projects would generate an estimated $3.7 million in annual revenue for the city, county, schools and other local agencies, according to consultants hired by Greenheart. A study commissioned by the city on Measure M concluded the initiative would have a chilling effect on future developments and create a competitive disadvantage for Menlo Park as neighboring cities don’t require voter approval to raise development limits.

This hasn’t deterred Measure M supporters like JoAnne Goldberg, who is alarmed by the size of the proposed office buildings.

“This is a very desirable place. This is not upper Siberia!” said Goldberg, a long-time resident. “People want to be here, and they want to develop here. I don’t think it’s unrealistic to try to balance expectations so that developers can make a profit but there’s also something in it for the residents.”

Goldberg said everyone agrees the large vacant lots along El Camino need to be developed, but not with “gargantuan office parks.”

“Right now, the projects that we are looking at are so huge it’s going to be a ton more traffic,” Goldberg said. “We are just trying to keep our lives from slipping further and further. And it’s getting worse every year.”

Marc Hayden takes an opposing view to his neighbor, Goldberg. He said Menlo Park voters shouldn’t be forced to vote on complex zoning issues they don’t have the time to fully understand. Hayden said he trusts the city council’s negotiations with developers and would resent the delay that Measure M would impose on projects to develop the vacant lots on El Camino.

“Nothing is going to happen if we go down this road,” said Hayden, who works in real estate, and believes most residents want a city where they can live and work. “We absolutely should be able to control our destiny and I think we’ve done so. I just don’t buy it that big money is trying to get us. I want to live with my children in a place where we can be progressive.”

Hayden and Goldberg participated in some of the 90 public meetings that the city held as part of its $1.7 million planning process to revitalize the area, with a final plan approved in 2012. Menlo Park’s median house price is $1.5 million, but closed storefronts haunt the posh boutiques and restaurants downtown on Santa Cruz Avenue. The Stanford and Greenheart project sites are just blocks away from those struggling businesses, and city council member Peter Ohtaki believes that proximity would help bring new customers.

“The proposals have a 50-50 mix of office and apartments,” said Ohtaki, who is running for re-election, at a recent voter forum where Measure M dominated the conversation. “That means a daytime and evening population that could become new customers for our downtown merchants.”

Ohtaki and two more city council members running for reelection are against Measure M, while three challenger candidates support it.

Candidate Kelly Fergusson regularly pushes for the initiative at the Sunday farmer’s market. She said Measure M is a “last resort” because the current council ignored concerns by residents.

“On these development sites we are building for generations, for a hundred years,” said Fergusson, a former Menlo Park mayor. “We need to get a balanced mix of uses right so that it serves the residents, not just line the pockets of wealthy investors.”

Mayor Ray Mueller said the city council is achieving concessions from developers for the community and that Measure M is unnecessary.

“The question is whether or not (residents) trust us to mitigate traffic. And we are drilling down on traffic and making improvements,” Mueller said in a telephone interview. The city council recently called for Stanford University to scale down their proposal — the largest under review — after a study showed it would significantly increase traffic congestion. Stanford is waiting until after the election to determine whether it will submit a new proposal.