At Phillips Brooks Elementary School in Menlo Park, students arrange spaghetti, string and marshmallows to concoct freestanding towers, following the same design-thinking process as Stanford University undergraduates.

In the school’s science classroom, yellow, blue and orange sheets of cardboard are scattered on the floor, as fourth-graders experiment with principles of ideation, prototyping and testing to remake a rocket until it’s ready to launch.

Being able to come up with an idea, “take feedback in a positive way, give feedback in a positive way, and then work on it again” is pivotal to a child’s growth, said Meeta Gaitonde, a former Phillips Books teacher.

For years, high school students in Silicon Valley have been exposed to the mindsets of innovation and creative problem solving. But now these lessons are trickling into elementary schools. Next school year, Phillips Brooks plans to implement an inventions program in which students will identify a problem and build a solution. The Nueva School in Hillsborough and Sea Crest School in Half Moon Bay are creating innovation labs for students as young as preschoolers.

Similar examples can be found in Australia, Brazil, Japan and South Africa.

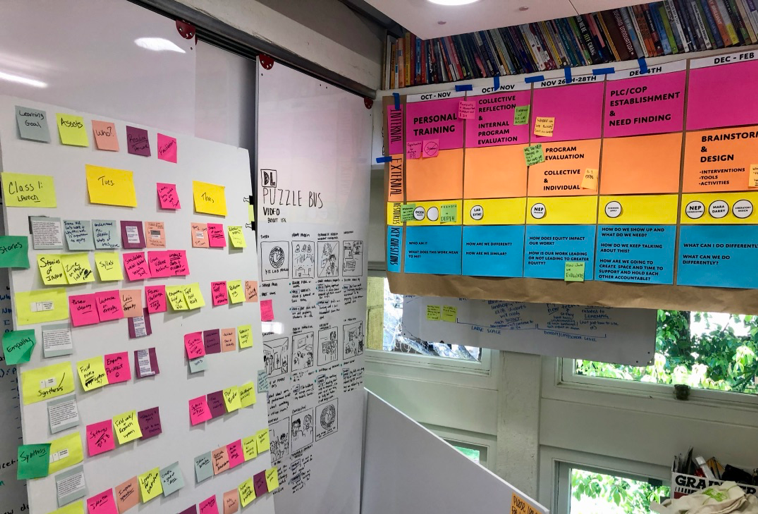

Design thinking is a problem-solving process that involves five steps: empathize, define, ideate, prototype and test. Stanford’s K12 Lab, located in the d.school, is known worldwide for incorporating design thinking and entrepreneurship into teaching.

Phillips Brooks students engage in lessons and activities for each step of the design- thinking process, according to Lane Young, the school’s director of educational technology. Two-thirds of fourth-graders can already describe the five steps, Young said.

Gaitonde believes that design thinking, through iteration, helps children feel comfortable while boosting confidence in their ability to address complex challenges. Carol Dweck, a leader in developmental psychology, has found that students with a growth mindset — believing they can improve through effort — typically outperform peers with a fixed mindset, which is defined by perceiving intelligence as a fixed trait.

As kids get older, they begin to develop an “inner critic,” said Ariel Raz, an experience designer at the K12 Lab. Design thinking gives them the confidence to propose ideas that are “out of left field … and more creative,” he said.

Beyond notions of individual intellect, design thinking is used to teach children how to understand people, their needs and their personal place in the world. Fifth-grade students at Phillips Brooks interviewed kindergartners about what games they were missing at the school; then they used the design process to build an arcade for them.

“The empathy portion changes the way students look at the world,” said Maureen Carroll, past research director of Stanford’s REDlab, which studies the impact of design thinking on education.

Regina Shields, a child psychologist in Oakland, said she likes the idea of design thinking in early development because it “truly sparks creativity.” By engaging the senses and taking an active approach to learning, children will be more involved in the learning process and form a deeper understanding of the material, she said.

“The best way for children to express themselves is through play,” Shields said.

But Shields and others are aware of potential challenges with implementing design-thinking projects into an elementary classroom. In particular, all children have varying levels of psychological maturity. An open-ended approach to learning may not suit students who are more susceptible to distractions in the classroom. A child with a low-frustration tolerance could have a tantrum during the building and testing process. A looser curriculum would require teachers to regulate students’ internal states.

Much of the design process involves communicating and defining a problem through interviews, which can be difficult for young children, according to Raz.

One challenge for educators is fitting design thinking into a traditional curriculum or school schedule. Design thinking “resists standardization” and is “non-traditional,” Raz said. Many teachers do not have the flexibility or the resources to take on design- thinking projects.

Planning, evaluating and grading an open-ended problem-solving process without a traditional rubric can also be a hurdle for teachers. Raz said, “It’s just… really messy. And that’s what’s cool about it. If you want to create something new, you’ve got to be comfortable with the ambiguity.”

Design thinking resources are becoming increasingly available. The K12 Lab provides free lesson plans for educators to take on low-cost design projects. For instance, its Foil Challenge asks students to get in pairs, identify a partner’s favorite food, and build a utensil for her or him using an aluminum square.