Every year during his annual physical, Bart Charlow hears the same thing: eat a healthier diet and exercise more. Despite serving as CEO of Samaritan House, a nonprofit that, among other services, manages medical clinics across San Mateo County, Charlow dismisses the usefulness of such trite advice. “Do you know how much of that diet and exercise I actually follow consistently? Just saying to someone ‘you need to control your diet’ … well, good luck with that,” he said, laughing.

Pioneering a new approach to such health challenges, clinics and hospitals are now offering a different kind of medicine – a prescription for healthy food every week. Known as “food pharmacies,” these on-site pantries are stocked with an array of fresh produce, whole grains, dairy and lean meats.

In the last year alone food pharmacies have opened up in Silicon Valley and Central Pennsylvania. This year, the Tom Waddell Health Clinic near the San Francisco Civic Center debuts its own food pharmacy in partnership with UCSF, to be followed by five other clinics across San Francisco by the end of 2017.

Food pharmacies as a new model

Dr. Rita Nguyen, health officer at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, says the goal of food pharmacies is to give patients better access to healthy food and teach them how to cook it once they have it. These programs primarily target low-income patients with chronic diseases like diabetes who receive weekly access to free foods aimed at keeping their disease under control.

The new San Francisco food pharmacy will seek to replicate the success of a pilot program launched at the Maxine Hall Health Center last year. Run by hospitalists from San Francisco General Hospital, volunteer staff from SF-Marin Food Bank, a registered dietician and students, the pilot program opened Friday afternoons.

Unlike a regular food pantry, the food pharmacy operated like a farmer’s market where patients could choose from a selection of healthy foods. While there, they could sample tastings from live-cooking demonstrations and talk about meal prep, nutrition and cooking tips with a health coach.

Many doctors embrace such efforts to promote healthy eating. Dr. Anne Rosenthal, associate medical director at the Maxine Hall Health Center, said, “as a doctor, I prescribe pills for diabetes many times a day. I can’t tell you how good it feels to prescribe green beans and carrots instead of medications.”

Spreading across the country

Across the coast in Central Pennsylvania, Geisinger Health System expanded its Fresh Food Pharmacy in March after a successful pilot of 180 diabetic patients starting late last year. The program is now adding 50 new patients each month.

Dr. Andrea Feinberg, medical director of Geisinger’s health and wellness division, has set her sights on an ambitious future for the program. Feinberg and her team are tracking patient outcome closely, hoping to publish the results, and eventually to persuade insurance companies to cover the cost of the food program.

Feinberg wants to set a successful example for the medical community to invest more on food instead of immediately prescribing medication. Currently, food costs the company $3 a member per week. For a four-person household, that’s less than $600 a year. There are also additional operational costs, including storing perishable produce and staffing a nutritionist and program manager.

Within just three months, patients enrolled dropped their hemoglobin A1c levels, in a test that measures blood sugar levels over time, by an average of two percent. Many started at around 10 to 13 percent, about twice normal levels. Lowering A1c reduces Type 2 diabetes complications, and healthcare costs – the data estimates this decrease saves them about $16,000, possibly more in the long run.

Feinberg previously worked in critical care for 25 years and saw the devastating and costly effects of treating chronic disease too late in the game. Patients with 20 years of diabetes come into emergency care with heart attacks, kidney failure, amputations and many other avoidable complications. “This is sick care, not wellness care. Our system has completely failed them. If we don’t come up with a new way to help people help themselves we’re not doing what we’re supposed to be doing as physicians,” she said.

Hospitals around the country have taken notice. Feinberg says she’s received calls from many doctors and medical staff, asking how to set up their own food pharmacies. “From the East Coast to Hawaii, people are calling,” she said.

Addressing behavioral change

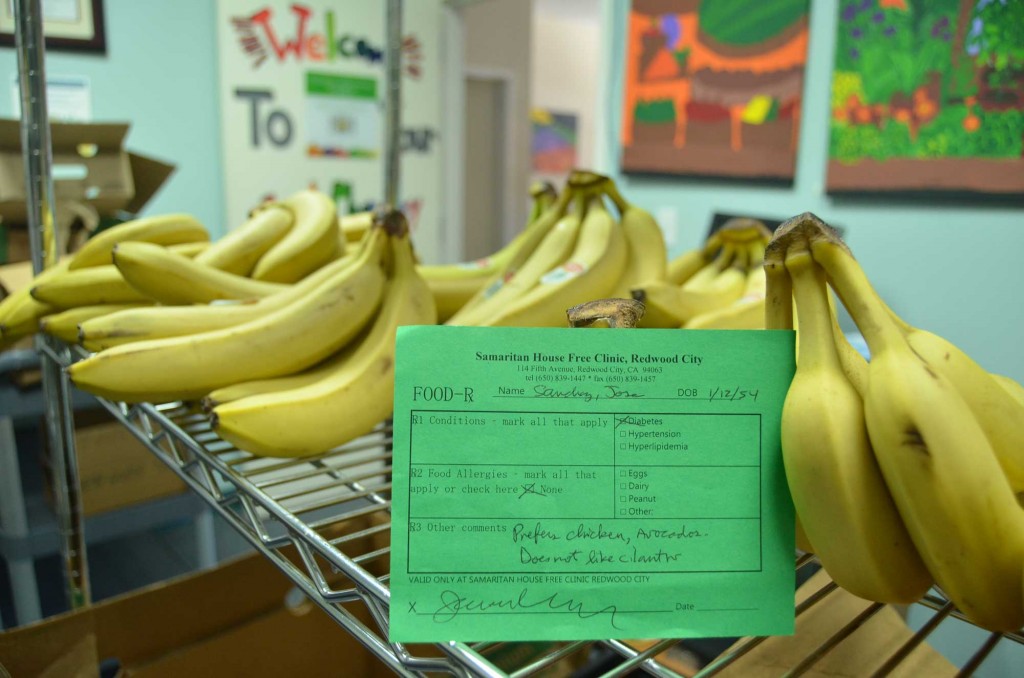

Other health systems may have fewer resources and research than Geisinger Health System, but express the same interests for their patients. In San Mateo County, Samaritan House has already served over a million meals every year for their low-income clients, but now their diabetic patients in both the Redwood City and San Mateo clinic have a steady supply of weekly healthy food they can rely on.

Decorated with brightly colored murals of fresh produce painted by local middle school students, the Redwood City clinic’s room is equipped with two industrial-sized refrigerators that store chicken, eggs, dairy and fresh produce like portobello mushrooms and onions. Along the perimeter, tall shelves display neat stacks of brown rice, quinoa, canned tuna and other healthy options.

Before the program, Dr. Jason Wong, medical director of the Samaritan House’s Redwood City Free Clinic, said it was difficult getting their patients to follow through with advice on lifestyle changes. But with about half of all U.S. deaths from heart disease, stroke and Type 2 diabetes linked to a poor diet, medical systems can hardly afford to ignore the importance of food.

What’s more, those with diabetes are three times more likely to worry that their food supply will run out compared to healthy adults, further exacerbating the disease and costs. In the past, food banks have struggled to keep junk food donations at bay with the reasoning that any food is better than no food. The result: low-income folks seeking help may end up with bags worth of sugar-laden, packaged, “empty calories.”

Samaritan House CEO Charlow says the results from their program have been “consistent and profound.” Patients enrolled have lowered their weight, blood sugar levels and blood pressure. To him, food pharmacies are “a no-brainer.”

A change in tide on nutrition in medical education and practice

Food pharmacies are part of the trend to shift greater focus on food in medicine. This starts with how medical schools train the next generation of doctors.

Christopher Gardner, professor of medicine and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, says “doctors themselves are an important target population in all of this. We want them to practice what they are then able to preach.” (EDITOR’S NOTE: Peninsula Press is a project of the Stanford Journalism Program in the School of Humanities and Sciences and not associated with Stanford Medicine.)

Yet historically nutrition education in medical schools has been scant. A few years ago, Gardner was asked by the Stanford Medical School to teach its students nutrition in four, one-hour sessions. “I thought, cool! And I asked them, ‘how about the second quarter?’ and they said, ‘that’s all the time you get in total.’”

Since then, Gardner and three key physicians have been working to address this long overlooked subject. They’ve updated the online curriculum and introduced “culinary medicine,” with hands-on courses that teach med students how to cook healthy food so they can effectively counsel patients to make their meals instead of relying on packaged and processed foods.

Even Stanford Hospital’s in-house food services have gotten a major revamp. When Helen Wirth, administrative director of Stanford Health Care’s hospitality services, first visited the cafeteria in 2013, she was dismayed. The most popular thing on the menu was deep-fried chicken fingers wrapped in iceberg lettuce and ranch dressing.

Wirth has transformed the food offerings to be “more reflective of health care and the Stanford brand.” Now, the cafeteria makes six house-made entrees daily, such as roasted antibiotic-free chicken wrap with avocado spread and light dressing. For a quick grab-and-go option, they’ve also planted upscale fresh-food vending machines offering things like sandwiches from local artisan bakeries and fresh-pressed juice around the hospital.

As it turns out, good health is good business, too: food revenues have increased by 15 percent and patient satisfaction has jumped to 140 percent over the past year.

Despite the food pharmacy model’s promise, Michelle Mello, Stanford professor of health research and policy, is skeptical about its financial feasibility. Insurance for low-income families like Medicaid are “stretched so thin to provide basic care for everybody that it is often hard for them to justify adding a benefit like food that seem less important than some of the core benefits that they’re struggling with. So I think it is a hard sell.”

Nevertheless, Gardner and food pharmacy program directors are optimistic. “Something seems to be moving forward. Medical systems have changed more in the last five years than in the last 50 years,” he said.