As the number and sophistication of cyberattacks increase, so does the demand for people who can prevent such digital incursions.

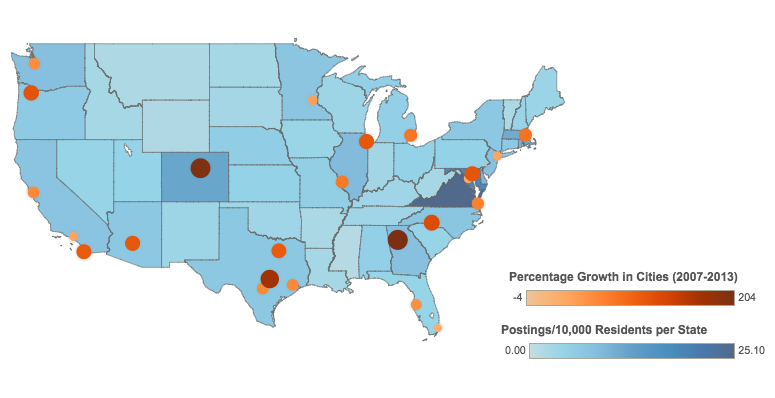

More than 209,000 cybersecurity jobs in the U.S. are unfilled, and postings are up 74 percent over the past five years, according to a Peninsula Press analysis of numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The demand for positions like information security professionals is expected to grow by 53 percent through 2018.

“The number of jobs in information security is going to grow tenfold in the next 10 years,” said Virginia Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe, director of the Jay Pinson STEM Education Center at San Jose State University, which mentors youth to enter and excel in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) careers. “We have to do much more if we want to meet that demand, at the university level as well as K-12.”

But educators like Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe are finding it difficult to teach students about cybersecurity fast enough to keep pace. Demand for cybersecurity professionals over the past five years grew 3.5 times faster than demand for other IT jobs and about 12 times faster than for all other jobs, according to a March 2014 report by Burning Glass Technologies in Boston, which develops technologies designed to match people with jobs.

This growing demand is leading to better salaries for information security professionals compared to other IT jobs. According to the same report, cybersecurity jobs on average offer a premium of about $12,000 over the the average for all computer jobs — the advertised salary for cybersecurity jobs in 2012 was $100,733 versus $89,205 for all computer jobs, says the same report.

Organizations across industries like finance, retail and education are looking for skilled professionals to design and implement comprehensive information security that covers a wide range of business security priorities.

But there is concern that there are not enough people in the pipeline to meet this demand. Among the issues: not enough young people interested in the field and not enough women.

The numbers back up the worries. Most of the jobs in tech and cybersecurity are held by men. And a 2013 survey by defense tech company Raytheon Co. found that fewer than a fourth of millennials are interested in cybersecurity and related careers.

The push for cybersecurity education

A handful of nonprofit and for-profit groups have been working to address what they see as a national education crisis: Too few of America’s K-12 public schools actually teach computer science and related topics like cybersecurity.

Chitra Dasgupta, a teacher at Sylvandale Middle School in San Jose, is trying to change that. Dasgupta’s class of 16 children is the only class in the school of 900 students that is working with Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe and her team to get some basic cybersecurity training.

According to Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe and her teaching team, exposing students to STEM education early, and then introducing cybersecurity concepts, is key to training enough experts to meet demand. At Sylvandale for example, Dasgupta’s students learn how to protect themselves from phishing, how to identify malware, know how to distinguish between white and black hackers and can even speak intelligently about heatsinks, used to cool central processing units in computers and other hardware components.

If people aren’t exposed to the workings of computers from a young age, they have this fear of them, or they say ‘computers just aren’t my thing’ and they give up.

“If people aren’t exposed to the workings of computers from a young age, they have this fear of them, or they say ‘computers just aren’t my thing’ and they give up,” said Nina Levine, an AmeriCorps VISTA member working with Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe. “If that’s the sort of mentality we raise our kids with, we’re never going to have enough people to fill the job market.”

“[Cybersecurity] may not be something that K-12 educators think of as essential, or at the forefront of their minds to integrate into a STEM program, which typically involves just robotics or programming,” Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe said.

For the students at Sylvandale — a school that receives Title I funds to assist in meeting the educational goals of its large concentration of low-income students — this introduction to computers is crucial. Many students [come from low-income families and] don’t have regular access to computers, said Dasgupta. The cyber-education they receive now could help them secure lucrative jobs down the line.

Today, most U.S. schools offer courses on how to use technology, but not courses that cover the fundamental concepts and skills of computing. In fact, only 19 percent of U.S. high-school students take a computer science class, a percentage that has fallen over the last two decades, according to the National Science Foundation.

Clearly, more education is needed to entice young people to pursue careers in the cybersecurity space. This is important because the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium reported in 2013 that existing IT security professionals are feeling overwhelmed due to staffing shortages, which could lead to more data breaches.

Correcting the gender imbalance

Another part of the cybersecurity narrative also is changing. Along with the push to include cybersecurity training in school curricula, many in the information security field are encouraging more female students to consider careers in cybersecurity.

Nearly three quarters of U.S. workers in computer and mathematical occupations in 2013 were men, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and gender inequality in Silicon Valley was at the forefront of discussion at this year’s Joint Venture Silicon Valley “State of the Valley” Conference. Large companies like Google and Facebook Inc., for example, have been embroiled in a debate over the lack of female employees, after data showed that women made up less than 40 percent of their workforces.

“Computer science isn’t glamorous,” said AmeriCorps VISTA member Philip Ye, who taught a cybersecurity class at the all-girls Monroe Middle School in San Jose. “Popular culture always portrays [cyber-professionals] as nerdy males who live in their mom’s basement, drinking Mountain Dew out of the bottle with chips all around them. So girls have already developed this resistance to it.”

But success in this field is often just a matter of tweaking the subject matter to appeal to the students, Ye added.

Data from the federal Department of Education shows that in 1983-84, computer science degrees accounted for 2.4 percent of all bachelor’s degrees conferred to women. By 2011-12, that had shrunk to less than 1 percent.

This is an especially notable trend because it runs counter to what’s been happening in other scientific fields.

According to research conducted by Randy Olson, a Ph.D. candidate in Michigan State University’s computer science program, the share of degrees granted to women in biology has risen from just under 50 percent to just under 60 percent over the same period. In the physical sciences, it has gone up from just under 30 percent to about 40 percent. And in engineering, it has risen from about 14 percent to 18 percent.

So why are fewer women in computer-related fields? Nina Levine, who also taught the all-girls class with Ye, hypothesizes that certain stereotypes might be part of the reason.

“We work with K-12 students and we see that at a younger age, all genders are equally interested in tech,” Levine said. “But as the students get older, the males stay interested, and the females, if they’re not encouraged to maintain that interest, they lose it.”

Further, many technology companies have an infamous ‘frat boy’ atmosphere that may not be welcoming to women, says Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe. But that is changing.

Network security company Palo Alto Networks Inc. in Santa Clara is one bright spot. The male-to-female ratio is about 50-50. The company is diverse and well-balanced, according to administrative assistant Ashley Valesquez.

But companies such as Palo Alto Networks are still relatively rare. In general, the data show that females account for only about 25 percent of the personnel in the field. In cybersecurity, only 10 to 15 percent of the workforce is female. Boosting that number could go a long way in closing the gap between supply and demand.

“I think it will take some very, very strong women to persist [despite this mindset] and keep their eye on the contribution they can make,” Lehmkuhl-Dakhwe said. “A diverse community only strengthens the product, and when I see both men and women embracing the need for diversity, it gives me hope.”