When manufacturing engineer Julissa Ramirez was looking for a job in Silicon Valley about three years ago, she got a stark reminder of the pay gap between men and women. Most companies she applied to offered her “a lot less” than her husband’s salary, also an engineer but without a masters degree like the one she holds, she said.

“The fact that I was getting offered a lot less than him was a big deal,” said Ramirez, 29, president of the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers in Silicon Valley. “We are equal partners and we bring equal amounts of creativity and innovation to the workplace, so we should be paid equally.”

As a new proposal to close the gender wage gap awaits its first hearing in the California legislature, Latinas in the region may have much to gain from the approval of this bill, the California Fair Pay Act.

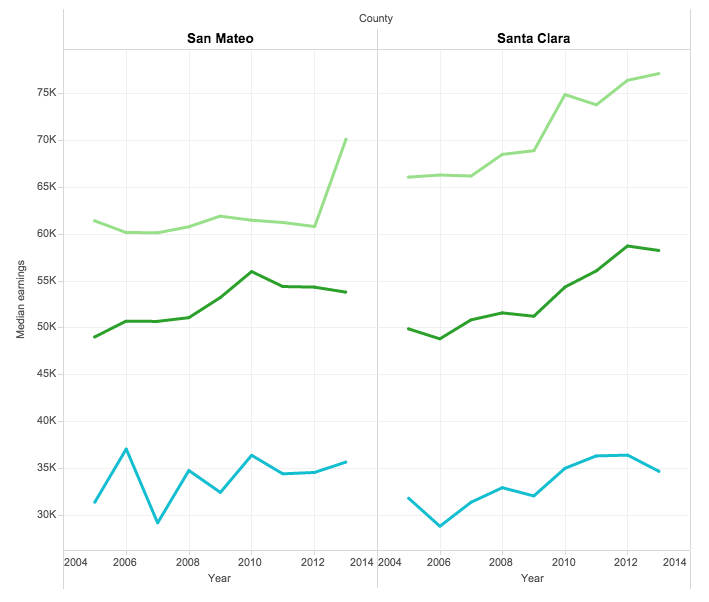

In Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties, Latinas working full time earned just:

- 35 percent of the salaries of white men, historically the top earners;

- 44 to 50 percent of the median salaries of all men;

- 49 percent of what white women earned.

Nationwide, Latinas are paid the least when compared to any other gender-race pairing of workers. While women in general earned 78 cents for every dollar earned by all men, Latinas made only 60 cents, according to the most recent figures.

The high concentration of Latinas in low-wage jobs throughout the nation explains only part of the disparity, said Noreen Farrell, executive director of Equal Rights Advocates, based in San Francisco.

“There’s also an intersection of race and sex discrimination in every workplace. Especially in workplaces with very few Latinas in management positions like technology and finance,” said Farrell, pointing to Silicon Valley’s concentration of both sectors.

Recent disclosures by large companies show that only a third of employees at leading technology companies such as Google and Facebook are women, while Latinos represent only 3 percent of the workforce there.

Contributing to the wider wage gap for Latinas are the relatively high wages in the technology field, which drive up the median income in the region for men. Software developers, for example, earn median salaries of over $132,000 according to state estimates.

The California Fair Pay Act would require employers to pay equal wages to women doing comparable work of male colleagues, and strengthen workers’ rights to openly discuss with employers the salaries of coworkers.

If approved by the legislature, Senate Bill 358 would add transparency in the workplace as pay secrecy is the main reason that workers don’t discover wage disparities, said Farrell, whose organization helped craft the bill introduced in February by California Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara).

“This would be the strongest fair pay law in the country, and really a first step in tackling discrimination as a major contributor of the gender wage gap for Latina workers,” Farrell said.

Though Sen. Jackson’s office has not received any formal opposition to the bill yet, proponents of SB 358 might face an uphill battle. Christina Villegas, a political science professor at California State University in San Bernardino, believes such a law would hurt women by limiting their options at work.

“If companies are afraid of being sued then they might be less likely to renegotiate compensation with women for flexible hours or reduced schedule, which is what a lot of women want of the workplace,” said Villegas, a visiting fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that states on its website that “government intrusion can lead to less economic opportunity for women.”

Villegas is concerned that SB 358 would hamper businesses she said are already overburdened by regulations, and in turn, discourage the creation of jobs filled largely by the working poor and minorities. She added that women facing discrimination already have the ability to sue employers because of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

However, San Jose resident Stephanie Bravo believes a law guaranteeing fair pay would help her job prospects after she finishes a master’s degree in education at Stanford University this summer.

Bravo, who co-founded StudentMentor.org and recently met with top education officials at The White House, wants to work as a director in higher education or nonprofits. But she is concerned that her ethnicity could play a role in unfairly limiting her wages.

“I’m highly aware that I’ll have to negotiate my salary,” said Bravo, 29. “It’s another level of things that I have to think about, when a white male doesn’t necessarily have to worry about that.”

Supporters of SB 358 expect the bill’s first legislative hearing in April and are hopeful that pay equity is gaining strong support amongst the general public. A 2013 national survey by the Women’s Voices Women Vote Action Fund and Democracy Corps found that ninety percent of voters favor raising wages for women to close the pay gap.

“It’s long overdue,” said Ramirez, who now works at Intel, a company she says does a better job at equal pay than others. “If there had been a law like that guaranteeing me fair pay at the time I was looking for work, it would have been easier.”

(Homepage image courtesy of 401kcalculator.org on Flickr via Creative Commons)