Four months ago, La Sonorense, a Mexican corner store and bakery in San Jose, was a typical store in the low-income Alma neighborhood. Monster, Red Bull and Rockstar energy drinks packed refrigerator shelves. Gatorade and sodas of all colors painted the store walls.

Now, green labels that read: “Good. To Go. Fun. Fast. Fresh.” point the way towards rows of V8 vegetable juice, bottled water and almond milk. The store’s owner, Consuelo Guevara, now offers a whole-wheat clone of a popular sugar pastry called “la concha.”

The green labels are just one component of Good. To Go.’s marketing campaign, a new program administered and funded by Santa Clara County’s Health Trust, an organization advocating healthier living throughout Santa Clara County and North San Benito County.

The Health Trust’s work is organized under three initiatives: healthy eating, healthy living and healthy aging. The Good. To Go. program — part of the Healthy Eating Initiative — aims to increase access to healthy food and beverages in low-income neighborhoods.

La Sonorense is one of 21 corner stores in Santa Clara County that has gotten a Good. To Go. makeover since the first renovated store opened in September. By 2016, the Health Trust — which has so far invested close to $1 million in the effort — hopes to transform 40 corner stores in Santa Clara County, promote mobile street vendors who sell fresh uncut produce, and increase the amount of farmer’s markets and urban gardens in San Jose.

-

Whole-wheat version of the “la concha” pastry at La Sonorense Bakery. (Austin Meyer/Peninsula Press)

Healthy corner stores project

Modeled after a successful Healthy Corner Store Initiative in Philadelphia, Good. To Go. aims to increase healthy food access by training store owners to market — and prepare — healthy food. La Sonorense got a new blender to make made-to-order fruit juices. Another store got a new refrigerator to store fresh produce. The broader goal is to change the eating paradigm in San Jose.

The challenges are stark. According to the Food Research and Action Center, a Washington-based nonprofit that is combating undernutrition in low-income area, residents of poor communities have fewer full-service grocery stores, more fast-food chains and are exposed to more advertising of unhealthy food compared to residents of wealthier communities.

“Any type of behavior change campaign where you are relying on people to make different choices is always a process,” said Erin Healy, director of the Healthy Eating Initiative. “I think there is a segment of the population that has gotten used to eating unhealthy foods for a variety of reasons — they’re busy or they don’t have the money to buy healthy. But I think there’s potential for change.”

Yacanex Posadas is the project manager for the healthy corner store project in San Jose. “There really are no options. It’s either soda or energy drinks. In terms of water, there is typically nothing.”

Good. To Go. identifies corner stores in food deserts — neighborhoods lacking major supermarkets — and store owners who are willing to make alterations to the layout and offerings at their stores.

When Carmina Rivera, owner of Emit’s Market on Almaden Street, agreed to take on the Good. To Go. brand, workers tore down shelves of processed food and built a table for fruit and vegetables in its place. They designated a refrigerator for qualified fresh products and introduced whole-grain and low-fat dairy options.

“I agreed to join the program because the health and welfare of the people is really important to me,” said Rivera. “It worries me to hear statistics about Hispanics, especially children, who are developing degenerative diseases like diabetes and hypertension at an early age,” because of diets high in sugar and sodium.

Good. To Go. incentivizes the purchase of healthy items by marketing them as fun and fast. Recipe cards for egg-salad sandwiches and tomato and tuna pasta nestle in plastic boxes next to rows of fresh produce, providing ideas for healthy home-cooked meals in less than 20 minutes. A yogurt popsicle snack takes five minutes to prepare.

From September through November, the Healthy Corner Store program offered $2 and $5 coupons on any items with the Good. To Go. label. The hope was that people would realize healthy items can be just as delicious and easy as chips or candy, and that when the prices return to normal, the new healthy habit would remain.

Initial indicators show how hard the challenge is. Of 35,000 coupons distributed via mail, door-to-door handouts, and at community events, only 101 were redeemed. Healy, who oversees Good. To Go., said that low return rate was expected.

It’s not only getting community buy-in. Karen Sepetis, owner of Good. To Go. corner store, Nature’s Best Market, says that the reason most small stores don’t sell fresh produce is because stocking the shelves is so difficult.

“My husband wakes up at three o’clock in the morning to go to farmer’s market in San Francisco to buy fresh produce,” Sepetis said. “If my husband didn’t do that I couldn’t provide produce. When you start at 3 a.m. and stay open until 10 p.m., you are working 20 hours a day.”

“It is easy to sell beer because a salesperson will come to my store, check my cooler, see what’s missing, order it, deliver it, set it up, and all I have to do is sell it,” Sepetis said.

Sepetis joined the program for publicity and to streamline her supply process. She hopes down the road that Good. To Go. corner stores can unify so that instead of ordering one case of produce for one store, they can order 100 cases for 50 stores, reducing costs, and subsequently, the prices in the store.

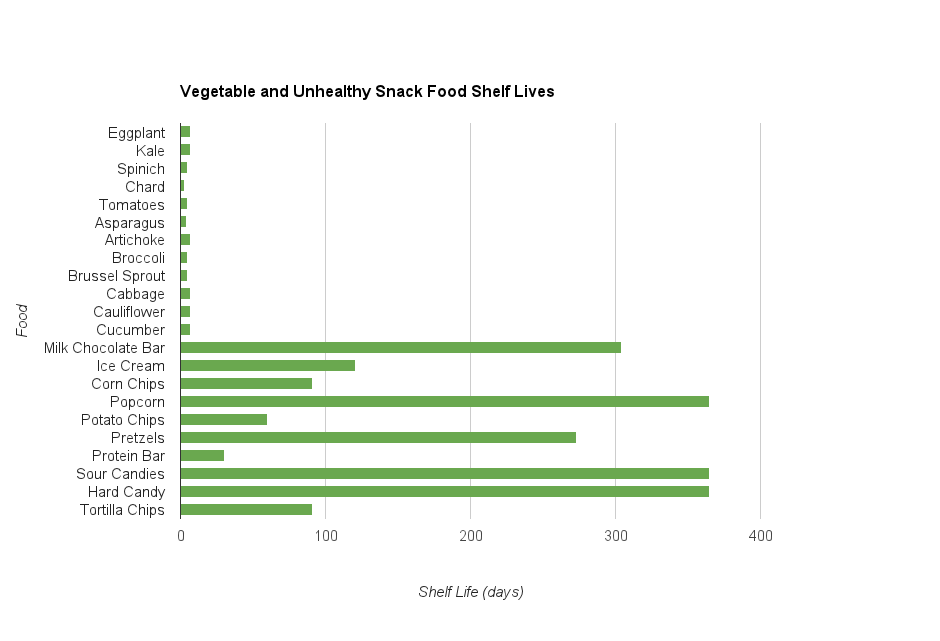

Another reason Sepetis says that stocking the shelves with fresh produce is difficult are the products’ short shelf lives.

In the back of Nature’s Best Market, a green trashcan is filled with withered greens. Basil leaves curl limply on top of each other. A speckled eggplant sits amongst shriveled peppers.

When wrinkles appear on vegetables because of the cool air used to keep them fresh, and tropical bananas blacken during a California winter, they go untouched.

“Every morning I go through the produce aisle and throw everything away,” Sepetis said. “People will not buy anything that’s not perfect and I can’t do anything to stop the process.”

But for Sepetis, members of the Health Trust, and everyone involved with the Good. To Go. project, overcoming the cost, access and awareness barriers to good health in low-income neighborhoods is worth the hard work.

“I will have somebody who will come and bargain for fresh fruit and then will buy 20 dollars worth of lotto, and not flinch, because it’s a dream,” Sepetis said. “But I am committed to selling fresh produce because it is sure health. If you don’t pay money now for your health, you will pay it later to become healthy, but you’ll pay it to the doctors.”